At Vashon High School’s commencement ceremony this Saturday, along with students in this year’s graduating class, a woman from the Vashon High School class of 1943 will receive the diploma she was denied 74 years ago.

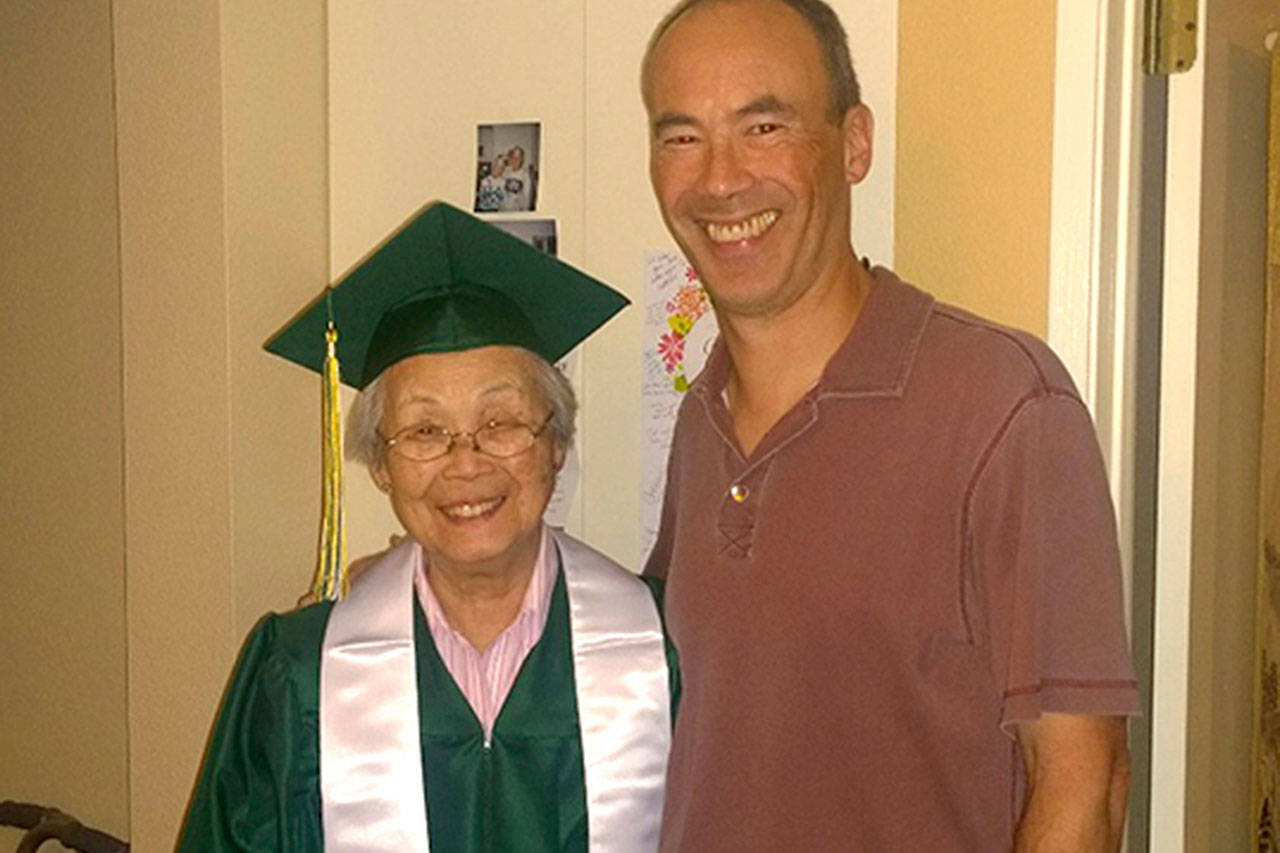

Mary Matsuda Gruenewald grew up on the island and should have graduated with her Vashon classmates, but instead she spent her senior year of high school with her family in concentration camps for Japanese Americans during World War II. The high school is recognizing this piece of history, and she will soon have a diploma from 1943, a development that came as welcome news to her. Gruenewald, now 92, recently said that she has had recurring thoughts of walking to the music of Pomp and Circumstance, assisted by her son, and receiving the coveted document.

“After all these years, I would love a diploma from Vashon High School,” she said in a phone conversation last week.

At the high school, Principal Danny Rock said a woman working with Gruenewald on creating a documentary for KCTS alerted him to the fact that Gruenewald would appreciate a diploma. School officials were happy to make that happen.

“As we got to know her story more fully, it became a relatively easy and obvious thing that we could do,” he said. “It was an obvious way to do our part to make amends and reparations for her internment.”

Because of some recent health challenges, it is unlikely that Gruenewald will be able to accept the award in person, but her son Ray Grunewald said if she cannot attend, the family will send a delegation to accept the award in her honor.

“She is thrilled,” he said. “This is something she has wanted ever since that time of her life (in the camps), yet she had never voiced it to me because she probably did not think of it as a realistic possibility.”

Mary Gruenewald moved to the island with her family when she was 2. Looking back at her years as a teen, she said she expects that growing up in Seattle was likely more exciting than growing up on Vashon. But she recalls Vashon High School as a wonderful place, where she enjoyed her teachers and fellow students. Her brother, Yoneichi, was two years older and an accomplished student, who was on the football team and a member of the student government; he graduated as the salutatorian.

“I coasted in on my brother’s reputation,” Mary Gruenewald said.

In her book “Looking Like the Enemy” about her family’s incarceration, she recalls her childhood on the island as one of innocence and pleasure — until it all changed.

“My parents chose to raise their family in order to protect us from the corrupting influences of modern life. But nothing could protect us from the events following December 7, 1941, the day Pearl Harbor was bombed,” she wrote.

Just months later — when Gruenewald was 17 — all the Japanese American families were forced to leave the island and were taken by train to the Tule Lake Concentration Camp in California. It would be three years before they were all free.

She recalls that before they were removed from Vashon, a neighbor went to Seattle and bought the family eight suitcases at Sears and Roebuck.

“Into that, we had to pack what we might need for an indefinite period of time,” she said. “I snuck in a small radio, shoes, pants, whatever I thought I might need. That was very, very difficult. What do you take when you do not know where you are going, what the climate is, how long you will be gone and if you will be coming back?”

Conditions in camp were harsh, and students attended bare-bones schools. Gruenewald says she recalls sitting on hard benches in the school room, with no textbooks for the students, paper or pencils.

Island historian Bruce Haulman said that school districts were responsible for providing instruction to children and teens at the concentration camps in their jurisdictions. Gruenewald, in fact, received a diploma from California’s Tri-State High School on July 16, 1943. She later wrote about that time.

“My classmates and I dressed up in caps and gowns and sat on benches lined up in front of the outdoor stage.

“If we had been living at home, we would have been looking forward to all kinds of exciting future possibilities: going off to college, getting jobs, working independently, getting married or traveling to foreign countries, just to mention a few. Despite the oppressive situation, we chose our class theme: ‘Today We Follow… Tomorrow We Lead.’”

Despite the bleak conditions of the school and the prejudices of the time, Gruenewald’s English teacher, a white man, saw her promise and encouraged her to apply for a scholarship to continue her education. She followed his advice and received a scholarship — a collection of money given by fellow Japanese Americans at the camp. She felt privileged to receive the funds.

“We were all destitute,” she said. “I do not remember how much it was, but it seemed like an extraordinary amount of money.”

Having worked as a nurse’s aid in the camp hospital, Gruenewald thought she might be interested in nursing and learned that the federal government would pay for her training in the United States Cadet Nurse Corps. She applied and was accepted into the program and for training at Jane Lamb Memorial Hospital in Clinton, Iowa, where her nursing education took place. With acceptance into a military program, Gruenewald was able to leave camp — by this time, Heart Mountain Internment Camp in Wyoming, and her parents moved to the Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho to be close to friends nearby. From there, Gruenewald traveled by train to Iowa. It was the first time she had ever been away from her family. She was 18.

“Here I am a kid off a strawberry farm from Vashon, taking a train to Chicago,” she said, recalling the trip.

Gruenewald said last week that her training there, over a period of three years, was excellent.

She went on to have a long career as a nurse. Ray Gruenewald noted that she also later attended college and earned her four-year degree in 1980 from Seattle Pacific University. But what was to have come first — a diploma from Vashon High School — had eluded her until now.

“It is a big, big deal,” she said. “It is something I have wanted and couldn’t have for many, many years.”