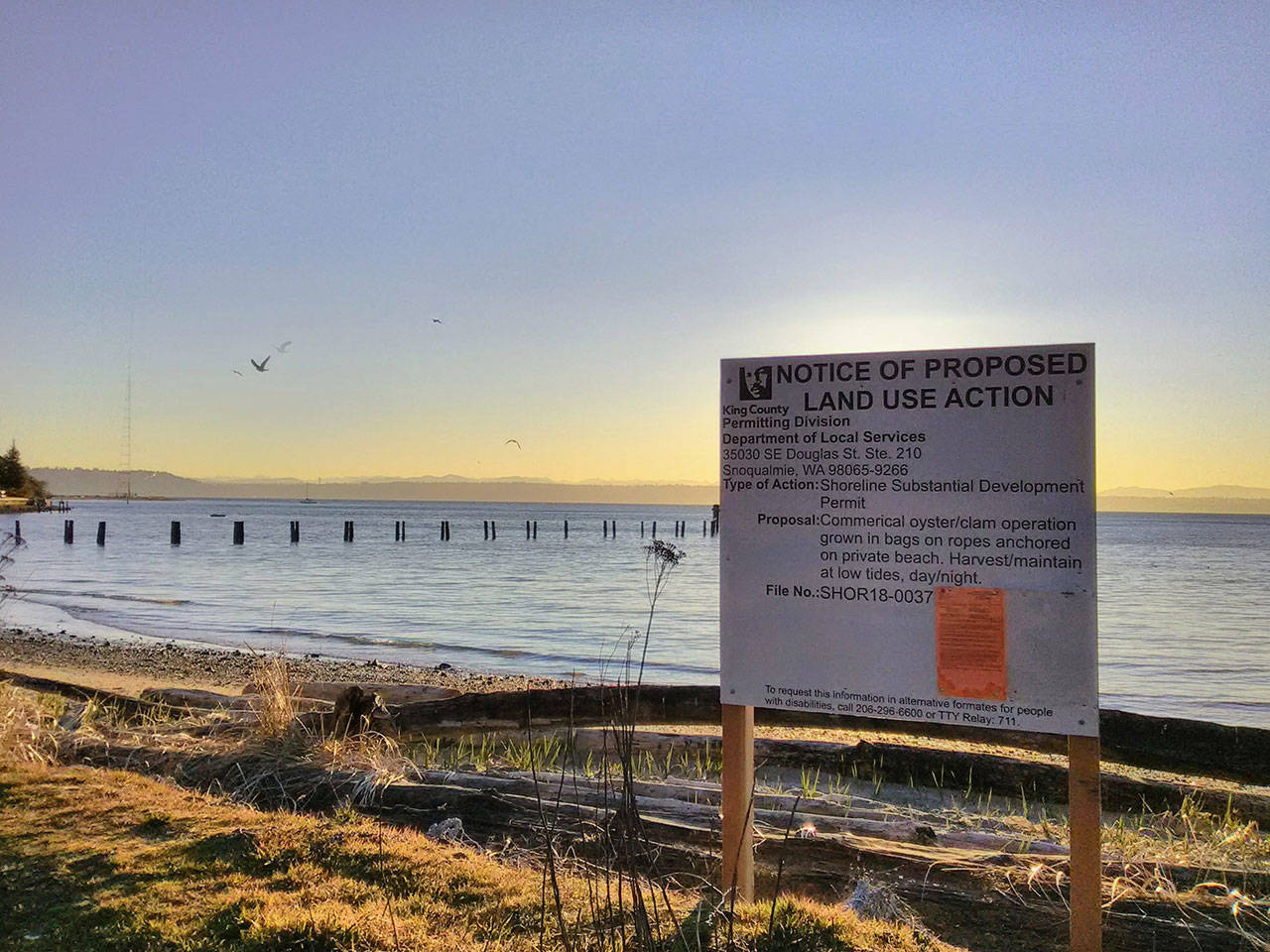

Island farmer Nick Provo is waiting for approval to start the only licensed commercial shellfish enterprise on Vashon in Tramp Harbor, but some islanders are concerned about the potential impact on native wildlife and say it will detract from the scenery.

Provo and business partner Ashton Kelley have proposed growing Pacific oysters and Manila clams from seed in floating flip bags strung across 16 lines 100 feet long in an area adjacent to KVI beach near the old wood pilings. Most of the lines would be submerged at high tide. Their company, Vashon Shellfish, is leasing more than 6 acres of inner shoreline from the Fuller family, who owns the land. The project is two years in the making, and he said his low impact and pesticide-free approach to cultivating the shellfish would require little, aside from a garden cart to push through the mud for collecting those ready for sale, a work table and headlamps to see on the occasion he and his workers harvest at night. Provo and Kelley hope to be in business by the year’s end.

“I’m committed to putting in a lot of labor into the operation. I’m not running quads up and down the beach — that means we’re pulling [shellfish] out ourselves,” said Provo.

He is used to getting his hands dirty. Provo bought property on Vashon in 2010 and built a house for his family there. Then he cleared the land, planted cover crops and grew soil until he could support an orchard, which now turns out raspberries, tomatoes, cucumbers, hot peppers and garlic.

“I don’t have any [prior] farm experience in agriculture, but I really like the ability to put the land to work and provide for myself, provide for the market, the community, [and] provide for my family,” he said.

A commercial shellfish bed on Vashon would be one of a handful like it in the county — the Puyallup and Muckleshoot tribes each have their own in Federal Way and Des Moines, and several regional aquaculture companies based throughout King County harvest at different locations, according to Scott Berbells of the Washington Department of Health. The tidelands surrounding the project site in Tramp Harbor are designated as commercially approved shellfish harvesting areas, according to county records.

Laura Casey, permitting division project manager at the Department of Local Services, said she has received comments from concerned islanders who wanted to know if the soil at the beach was contaminated from past industrial activity in Tramp Harbor, but she said no study about soil toxicity has been completed at this time as part of the project. She said the county will decide whether to allow Provo to proceed after the public comment window closes and additional input is received from the multiple agencies reviewing the project, including from tribal representation.

Once that process is complete, the project will have to be found in compliance with the standards of the county’s shoreline master program, which Casey said implements the state shoreline management act.

Provo said the decision can’t come soon enough. On the East Coast, he said, people have experimented with forming their own shellfish crop share associations — he would like to explore similar possibilities on Vashon in the future, along with direct-to-consumer sales, but his initial vision is modest. To start, he said he will seek out island restaurants and grocery stores as his primary market.

“Right now we’re just trying to get shells on the beach,” he said. “It takes a lot to figure out how we’re going to use [the land], what impact I want to have, and [that] might not [make] the biggest buck right away.”

Provo believes his shellfish could have a positive ecological impact — he said Tramp Harbor has no algae blooms unlike nearby Quartermaster Harbor, which is now closed to some recreational shellfish harvesting due to biotoxins.

“It can get really impressive currents to flush it out, so it hasn’t suffered the same problems like that,” he said.

Paralytic shellfish poison — detected as recently as last fall — resulted in a temporary ban on all shellfish harvesting on the island, but did not extend to commercial harvesting.

Provo added that when he attended a recent shellfish conference with fellow mollusk-enthusiasts, some displayed video taken underwater with GoPro cameras to document the changes the seabed underwent where they planted shellfish. He said he was amazed by what took place once the shellfish had grown.

“Essentially what you’re creating are underwater structures for fish and marine animals. The hope is that it creates some benefit out there.”

Shellfish are mighty creatures. An adult oyster can filter 50 gallons of seawater a day feeding on phytoplankton, simultaneously creating a healthy habitat for a plethora of species such as urchins, worms and juvenile fish, according to Teri King, a marine water quality specialist for Washington Sea Grant.

“It’s amazing what you find on or around [growing] gear. In a way it’s kind of like a reef,” said King. “You get a lot of organisms checking it out that like to be there, so it’s fun to watch.”

King said poor water quality has previously made endeavors such as Provo’s impossible on the island, but noted her admiration of efforts to eliminate sources of pollution once found here. With a career spent working with shellfish spanning decades, she added that commercial shellfish harvesting could be unforgiving for growers, and help is not widely available should something go wrong. For installations such as Provo’s, she said, planting sites need to be consistently monitored to check the bags in the event they threaten to tear from the line, and regular samples of the shellfish will be required. She said there is a lot of prediction involved, and much at stake, from managing the work to environmental stewardship and ensuring food quality.

“It’s not a get-rich-quick scheme, I promise. If anybody comes here and thinks they’re going to find gold, it’s going to take time.”

King believes native species will appreciate the presence of the shellfish, including birds, which she said may tend the area themselves in greater numbers than they do today, along with other flora and fauna, as supported by earlier research. But some islanders have criticized the project, believing that the shellfish bed may disrupt the ecological balance present at KVI as well as mar the beauty of the waterfront.

After a post about the project was shared on Facebook, many weighed in, arguing the shellfish would displace ducks and other birds that frequent the beach. They aren’t alone. Earlier this month, conservationists and the public in Humboldt Bay, California, questioned whether a major shellfish development there threatens native bird species, but that project, at 200 acres, directly encroaches on habitat and nesting areas favored by birds.

According to a marine survey, no federally listed endangered bird species will be affected by the project in Tramp Harbor. Ecologists surveying the site gave priority to the evaluation of critical fish habitat nearby, namely chinook salmon, Puget Sound steelhead and rockfish. They found no eelgrass — a lifeline for chinook and vital food source for numerous species — and concluded that the development would occur outside the elevation range of spawning herring, surf smelt and other forage fish.

John Stanton, director of technology at Vashon High School, said he was concerned about the potential impact on birds posed by Provo’s shellfish at Tramp Harbor, as well as the economic repercussions of such a development, as he said it may discourage tourists from visiting KVI Beach.

“I pass by on my way to work for the day, and for probably half the year it seems to be a bird paradise,” he said, noting that with the arrival of winter, the variety of birds flocking to the area drops off substantially. He wondered if the shellfish operation may inadvertently disrupt bird migration to the area if the food sources they depend on are suddenly affected, adding that he was aware the Vashon Audubon Society recognized Tramp Harbor as a significant birding location.

Randy Smith, Audubon’s conservation chair, said he had no knowledge of the proposed shellfish bed. But he noted the importance of that long stretch of coastline to the Audubon, and Vashon’s community of avid bird watchers.

“The whole area there, from KVI Beach down from Ellisport and down to Tramp Harbor, is rich with birds,” he said.

For his part, Provo said he is looking forward to supporting the island economy, calling it a paramount goal. He said he hopes his shellfish grown in Tramp Harbor will convince skeptics of the development’s merit in the years to come.

“As successful as we get, once we’re on that beach, we’re staying on the island.”

Comments

Islanders can submit comments to Laura Casey, permitting division project manager at the Department of Local Services, at laura.casey@kingcounty.gov until April 15.