Vashon and Maury Islands are home to more than 800 veterans, including Marjorie “Midge” Grace, who at 95, is likely the oldest Marine, and possibly the oldest veteran, in this community.

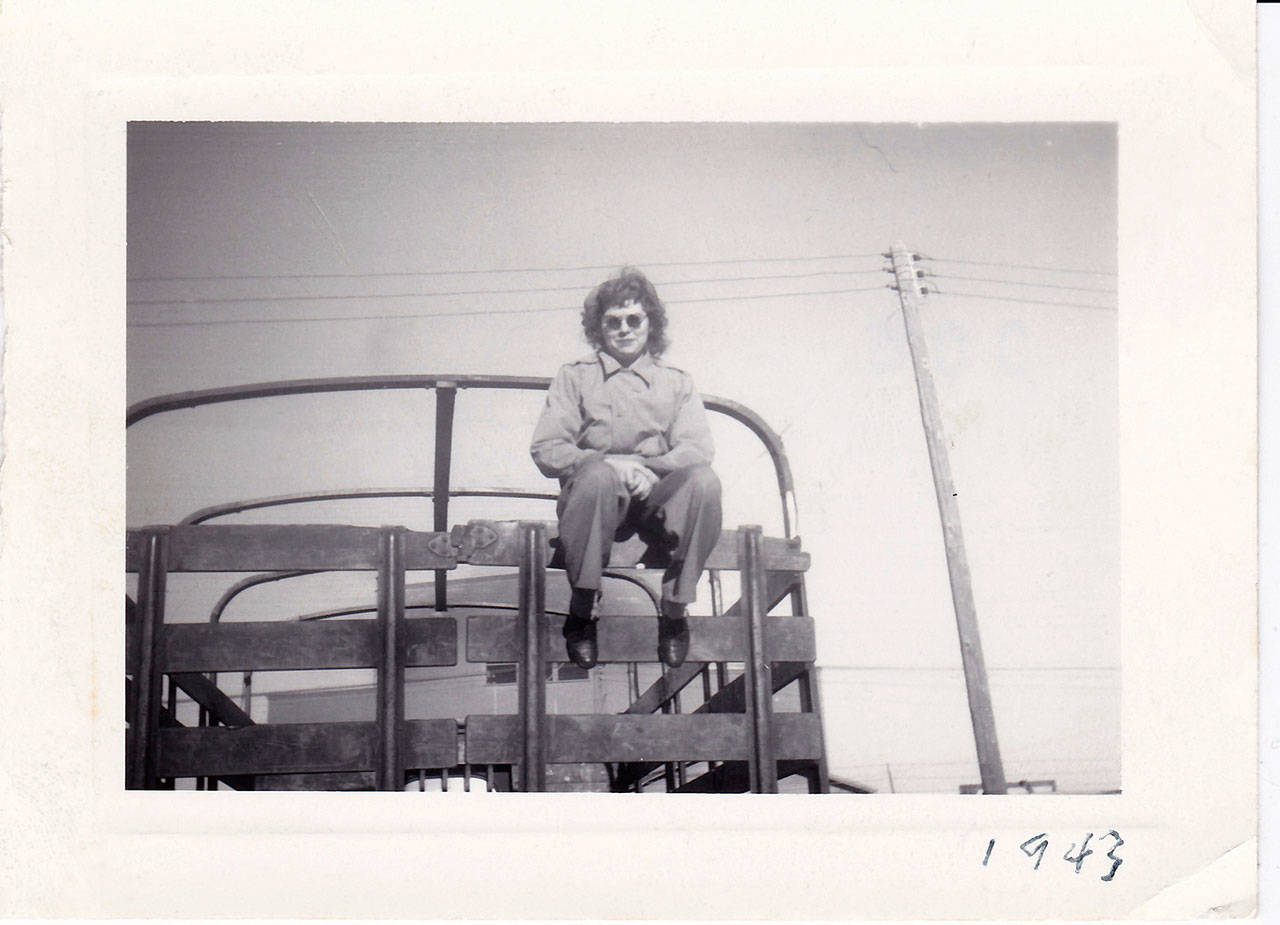

Grace stopped by The Beachcomber offices last week to share some of her recollections from her two years serving in the United States Marine Corps Women’s Reserve after enlisting on Nov. 10, 1943 — the 168th birthday of the Marines — when she was 20.

With World War II going on, the concepts of patriotism and self-sacrifice were running high, she recalled.

“I really, really wanted to join the Marines corps,” she said. “I felt I should, and I felt I could. I wanted to do something to serve my country.”

The opportunity for her to join the Marines was fairly new. During World War I, women were allowed to enlist in the Marine Corps Reserve, according to several historical accounts. More than 300 women did so; at the time, the messaging was that their service freed men up to fight.

During World War II, the Marine Corps created the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve in early 1943. Again the idea was that the women’s presence on bases would enable more men to fight overseas. Nearly 20,000 women served in the corps during the war years.

Grace grew up in West Virginia, and said she thought about joining the military as a way to leave the state. She had little family military background, she added, although her father, at 17, had lied about his age to enlist in the Army in the First World War. He was on the dock to go overseas when the armistice was signed. Other than her father, she was the first person in her family to serve in the military.

At 18, Grace married. By age 20, she was living with her in-laws in Oregon while her husband was in the service. She had completed her first year at Oregon State University and was working at Carbide and Carbon when she enlisted. Before the end of the year, she was in boot camp at the Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia.

“We marched everywhere,” she recalled of her two months there.

She was then sent to motor transport school, where she learned how to drive a different military vehicle each week. With training behind her, she was sent to Camp Elliott, a Marine Corps training facility in San Diego. There she drove a ton-and-a-half International truck, she said, charged with keeping it serviced and running well and with transporting “whatever needed to be moved,” people or supplies.

After about a year, her husband returned from overseas and was stationed at Fort Belvoir in Virginia. To be closer to him, she requested a transfer back to Quantico, where she was assigned to drive for a colonel. Part of her work involved testing vehicles and products that came to the Marine corps, including a memorable testing of night vision glasses, which were new at the time. At 21, she drove three colonels in her Jeep for the test, making them all nervous on the night ride.

“I was the first to use them,” she said of the glasses. “I had them on, but they did not. The test was to see how accurate you could be driving with only those glasses.”

She laughed at the memory.

“They were yelling because they did not know where they were going,” she said, mimicking their worried exclamations.

She also recalled once driving a tank, but that memory did not elicit as much laughter.

“It was scary. It was too much for one person,” she said. “But anyway, I did OK on it, and everybody lived.”

After about a year at Quantico, she was eligible for a discharge, but the war ended at nearly the same time.

“When the first bomb dropped, I was sitting on my bunk waiting for my discharge papers,” she said, adding she knew nothing about atomic bombs or even the word “atomic.” “But I knew as I sat there on my bunk that was the end of the war.”

Grace was quick to praise the women she served with.

“I have never met a nicer group of women than Marine corps women,” she said.

For many men in the military, having women join their ranks was unwelcome, and many were openly opposed. This attitude surprised Grace when she encountered it.

“I would have thought everybody would have welcomed you in,” she said.

She declined to elaborate about what she and other women in the Marines experienced, except to say, “Any women in the armed forces during and following World War II felt the brunt of the displeasure of the military men.”

Midge Grace has lived on Vashon for 12 years near her daughter Deirdre Grace and son-in-law Mark Wells. Deirdre says her mother lived a full and varied life after her years in the Marines. Her marriage to the man she married at 18 did not last, and she went on to marry five more times. She attended college on the GI Bill and earned her degree in fine arts from University of California-Berkeley. She lived all over the world, including New Mexico, Canada and South Africa. For a short time, she lived in Alaska and was able to vote on statehood there. Her professional life was as varied as her homes; she owned an ambulance service, launched and operated a successful waterbed manufacturing business, served as a court monitor and taught art for many years.

Last week, the talk turned to Veteran’s Day coming up. Midge Grace does not plan to recognize the day in any special way, saying she is not a “gung-ho” type of person.

But she followed up on that thought quickly.

“I was proud to be in the Marines. I really was,” she said.