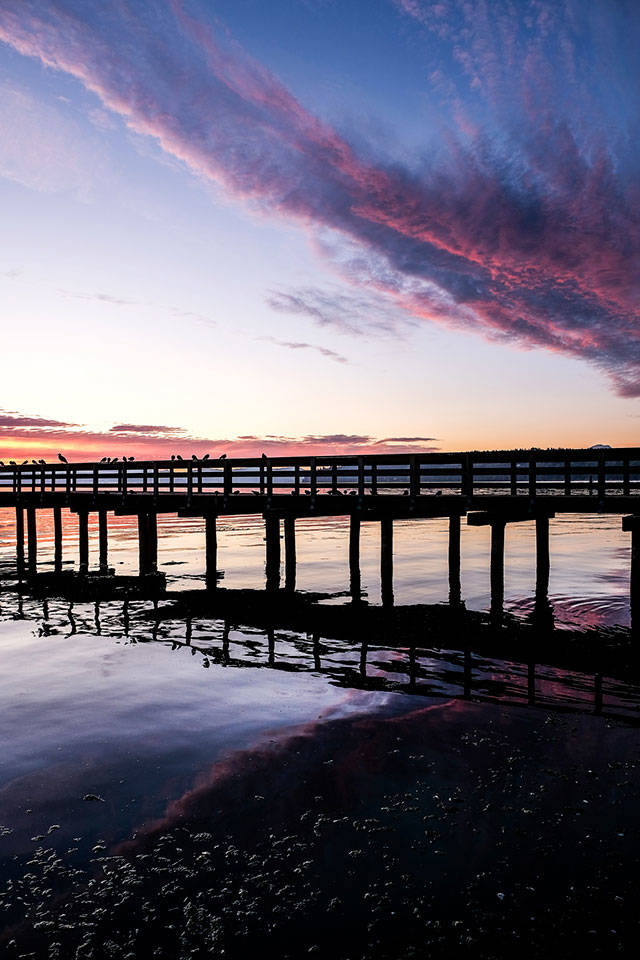

The Tramp Harbor dock, one of the island’s most recognizable waterfront landmarks, is set to close to the public following a recent mandate from the Vashon Park District’s insurance provider.

A chain-link fence will be erected across the entrance of the dock — a popular spot for fishing, photography and bird watching — as early as Dec. 2, along with the removal of several feet of planking to deter trespassing.

For years, the L-shaped, 340-foot pier, sticking out like a thumb across the water as cars race past on Dockton Road, has been vexed by a multitude of problems. The district cannot afford to repair or replace the historic dock and would be burdened with liability risks to keep it open in its current state. Commissioners now have the task of deciding how to proceed, and invite the public to discuss the circumstances with them during the board’s meeting at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 26 at Ober Park, when the district will also lay out its 2020 budget.

But executive director Elaine Ott-Rocheford said she does not anticipate that public input will sway the commissioners to vote against barring access to the dock.

“I feel like I’ve followed all of the threads, to the best of my ability, in understanding our risks and liability in an attempt to mitigate those risks — and hit a dead end,” said Ott-Rocheford in an interview with The Beachcomber.

She added that the district has hired an environmental attorney to explore any other insurance options that may remain, and to offer assistance for negotiating with the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR), which requires a lease with the district for the tidelands underneath the far half of the structure in order for it to remain standing.

At the last board meeting, commissioners agreed that while the outlook looked grim, they could not definitively say how the situation with the lease would ultimately play out. But it was clear that the dock’s closure was imminent.

‘Turn Over Every Stone’

There has been a dock in Tramp Harbor for generations. In the 1920s, the first automobiles to travel by ferry to the island landed there, between Portage and Ellisport. The ferry dock later served the island’s petroleum needs as the destination for products delivered by the Standard Oil Company, until it was converted into a public pier and later deeded to the Vashon Park District by King County in 1995.

Much of the uncertainty surrounding the dock can be traced to that exchange. When the county originally gave the dock to the district, it did not sign over the aquatic lands lease it had with the state for the tidelands under the latter 160 feet of the dock, including the platform at the end of the walkway. That left it unclear as to whether the district had agreed to accept all outstanding liability for the dock, such as the contamination posed by the creosote pilings, though Ott-Rocheford said as the current owner, the district incurs some responsibility.

The toxic leaching from the pilings into the tidal sediment is considered akin to a preexisting condition by the district’s insurance provider, and efforts to find coverage elsewhere have not yielded results. DNR will conduct another round of testing for creosote in Tramp Harbor later this month.

Meanwhile, the district is feeling pressure to sign a new lease with the state, but negotiations have only occurred intermittently since the prior 12-year agreement expired in 2013. Without an official agreement, the far half of the dock will need to come down.

Joe Smillie, a spokesman for DNR, said it is impossible to say when that would occur, should the district formally refuse to sign a new lease.

“I know the commissioners have a lot to weigh and consider, and whichever way they want to go with it, we’re open to helping out,” he said. “If they decide they don’t want to go through with signing the lease, we’ll see how to remove [the dock]. If they want to continue options for keeping it, we’re here to help, too.”

Earlier this year, both the district’s attorney and insurance broker advised against signing the latest draft of the lease proposed by the state. Doing so would have left the district responsible for all environmental liability as well as for the general use of the dock. Additionally, under that draft, the district would have to agree to fully protect DNR from nearly every kind of liability, a stipulation the district’s insurance provider said amounted to contractual liability and was an added factor in their recommendation.

“It’s time to make a decision about whether or not we’re going to enter the lease,” said Ott-Rocheford, adding that the state is motivated to find a reasonable solution. “I think we all agree that this needs to come to an end and that a decision needs to be made to move forward.”

In September, Ott-Rocheford optimistically shared with the board that the state had agreed to consider the district’s attorney’s edits to the draft lease, possibly leading to some liability relief for the district. But she said most of those edits have been rejected. The draft has been sent back to the district’s attorney.

“I want to make it clear that I am absolutely, 100% dedicated to following this through to the end in a way that everybody is absolutely satisfied [with], so the community is absolutely satisfied that we’re operating with truths and known risks,” said Ott-Rocheford. “I won’t rest until I feel that we’ve turned over every stone and we’ve done the proper due diligence in making our decision.”

Contamination from the pilings and the difficult lease agreement are not Tramp Harbor dock’s only problems. Warnings have been posted there for some time advising the public that it may be unsafe to walk on.

A 2015 engineering assessment concluded that nearly a dozen of the 96 pilings holding the dock up were in poor condition, and some were thought to be approaching failure. According to the study, at least 20 feet of the dock would likely collapse if any single pile fails.

The district last considered closing the pier at that time, but it was able to remain open with the warning signs in place.

Replacing all of the pilings would cost an estimated $312,000, said Ott-Rocheford, who noted that both former and current commissioners delayed action because they believed such a significant investment as replacing the pilings would prove worthless if the state moved to tear the dock down pending a decision to pass on the lease.

“The real story is that it’s just such an expensive facility to do anything with,” said Bob McMahon, the chair of the board, referring to the cost of repairs and creosote remediation. “It’s so far beyond the financial capacity of a little district like ours.”

He believes the district’s other commitments on Vashon — from the asset preservation work it can perform at its other properties with a limited budget, to the resources the district has for supporting programming — are just as important as saving the dock. But, unable to protect the district against risk, he said, commissioners have few options.

“As unfortunate as it is to have to close it, there’s just no alternative,” he said, adding that he suspects it will be up to the state to decide what comes next for the dock as the district cannot sign the onerous lease agreement.

Looking For Funding

Replacing the Tramp Harbor dock with a new public pier could cost between $1 to $2 million, according to Ott-Rocheford. She added that the most likely scenario for funding such a project would either come as an appropriation from the state, asking island voters to approve a bond or for a local 501(c)(3) to engage in a fundraising campaign on behalf of the dock.

The district could apply for some county and state grants, she said, noting that they do not cover engineering and permitting costs, which are significant.

“In the face of a grant, my estimation is we would still be responsible for an estimated $1 million worth of funding,” she said, adding that the district attempted to obtain funds to devote to work on the dock as part of their 52-cent April levy run that failed. No such funding was a part of the district’s recent 45-cent levy.

In September, Sen. Joe Nguyen (D-West Seattle) told The Beachcomber that the chances of securing a state appropriation to support work on the dock were slim, as the state capital budget for 2019-2021 was passed and signed by Gov. Jay Inslee in May. But he mentioned the possibility that $3 million previously secured by former Sen. Sharon Nelson in the 2018 capital budget — intended for Neighborcare Health to renovate the existing clinic at Sunrise Ridge or build a new one — could be appropriated for other purposes, such as intervening at the Tramp Harbor dock.

“The money is to make sure improvements or [construction of] a new facility could possibly have some state funding,” said Nelson, adding that it was not dependent on any single clinic operator offering services at Sunrise Ridge.

All members of the delegation that Nelson worked with to help draft the budget at the time, she said — including Representatives Eileen Cody and Joe Fitzgibbon — had seen the condition of the clinic and supported the measure to set that money aside.

“It was clearly the intent to have it available for the medical needs on the island,” she said.

In an email, Joseph Sparacio, Chief Development Officer for Neighborcare Health, said the organization does not plan to use the funds for improving the Vashon clinic at this time, deferring to the board of commissioners for the island’s newly-created hospital district to guide such decisions.

“We are awaiting the newly elected commissioners to come forth with their plans for funding health care operations on Vashon. Until we better understand those decisions, we cannot commit to any capital plans,” he wrote.

No one can say for sure if help for repairing or rebuilding the Tramp Harbor dock is out there, and if it is, where it might come from. But islander Jake Jacobovitch, a former commissioner of the Vashon Park District who was on the board during the transfer of the dock from the county, said he believes all stakeholders — local, county and state — need to continue having conversations about what direction to take next, and together decide if the expenses posed by the dock are worth it.

“When we entered into this arrangement in 1995 [with King County], it was with the understanding that we would be partners, that it was a partnership,” he said, adding that the dock was one of several properties the district took over from King County that year. Jacobovitch said he hopes the county will honor that commitment and be a resource for the district as it moves toward finding a solution. Even preserving some amount of the dock for light recreation such as fishing, he said, would be better than nothing.

But Bill Ameling, who served with Jacobovitch on the board at the time, said he doesn’t believe the district should fight the inevitable.

“If we didn’t have a dock, we wouldn’t put one there, let me tell you that,” he said. “Probably the best thing to do is tell the state, ‘you remove the dock,’ and just leave it at that.”

But islander Stefanie Marotta said that can’t be allowed to happen. She has lived on Vashon for only three years but is frequently at the dock where she said she has had no trouble making friends. She said she has seen scores of people young and old take in the picturesque sights or cast lines from the walkway over the railing in the summertime, making memories and exciting discoveries of their own.

“It’s been a real community kind of thing and a really interesting way to meet people. It’s a great place and it would make me really, really sad if they close it,” said Marotta, who said she was in shock when she heard the news. She encourages more people in the community to make their voices heard and stand up for the dock’s preservation.

“I love it out there, and so many other people do too,” she said.

This version of the article corrects the spelling of Stefanie Marotta’s name.