Once a year, a city of 70,000 souls seems to rise out of Nevada’s mud-cracked Black Rock Desert, remains for a week and then disappears. Called Black Rock City, the transient metropolis is the ephemeral epicenter of the cultural arts festival known as Burning Man. In the 30 years of its existence, the spirit and soul of Burning Man has eluded capture, due in part to its nature of creative change and in part to its experiential character.

Now, in the new photo memoir “Playa Fire: Spirit and Soul at Burning Man,” award-winning photographer and writer Stewart Harvey tells the story of the landmark arts festival, from its birth in 1989 on San Francisco’s Baker Beach to its current home on the desert “beach” of Black Rock City, through prose recollections and over 250 of his evocative photographs.

Harvey will share a slide show and talk about his new book at 6 p.m. Sunday as part of the Arts and Humanities lecture series at Vashon Center for the Arts.

As the brother of the festival’s co-founder, Larry, Harvey could be called the ultimate insider, witnessing and documenting the event first-hand. While dates and location identify the festival’s inception, its creation story, Harvey writes, begins with Larry’s broken heart after a failed romance and his decision to “expunge the pain of that memory … with a bold act of defiance and self-expression.”

The act was to build and burn a 15-foot wooden human effigy — hence Burning Man — on the eve of the 1986 summer solstice at Baker’s Beach. Though it began with a handful of “burners,” communal involvement quickly caught fire. Harvey recounts his unanticipated reaction to his first Baker Beach Burn in 1989.

“The intensity was genuine, the emotions were raw and the sense of being a part of something larger than life was very real,” he writes and then quotes his brother, who said, “‘Immediate experience is the most important touchstone of value in our culture. We seek to overcome barriers that stand between us and a recognition of our inner selves, the reality of those around us, participation in society and contact with a natural world exceeding human powers.’”

When a near disaster with the burning of the man occurred in 1989, combined with the growing popularity of the event, the co-founders moved the event to the desert the following year, a decision Harvey describes as highly beneficial for the festival’s longevity.

“I believe Burning Man exists today because of Black Rock Desert. It is a genuine sacred space. People begin to touch parts of their interior selves that are stowed away in the regular world,” he said. “The desert is a blank canvas, a great playground and an opportunity to express yourself. That is the heart and soul of Burning Man.”

Built on the twin foundations of self-expression and a supportive, participatory community, Burning Man draws participants from around the globe and is guided not by laws, but rather by 10 main principles: radical inclusion, self-reliance, self-expression, community cooperation, civic responsibility, gifting, decommodification, participation, immediacy and leaving no trace.

As seen throughout the images in “Playa Fire,” Black Rock City could be a set out of “Star Wars.” Fantastically inventive structures populate the area. “Art cars” are the only allowed motorized vehicles inside the city, and scores of people — tiny in the vast expanse — pedal bicycles, walk on stilts or perhaps shower under a sculptural tree.

The week of art happenings culminates in the burning of the man, now 42-feet tall, followed by the burning of the temple the next night. Each event, like an ancient ritual, evokes a separate response.

“The burning of the man is great, loud, noisy and spectacular,” Harvey said. “The temple, filled with personal memorials, artwork, photographs, is heartbreaking. Over 50,000 stand silent during the burn.”

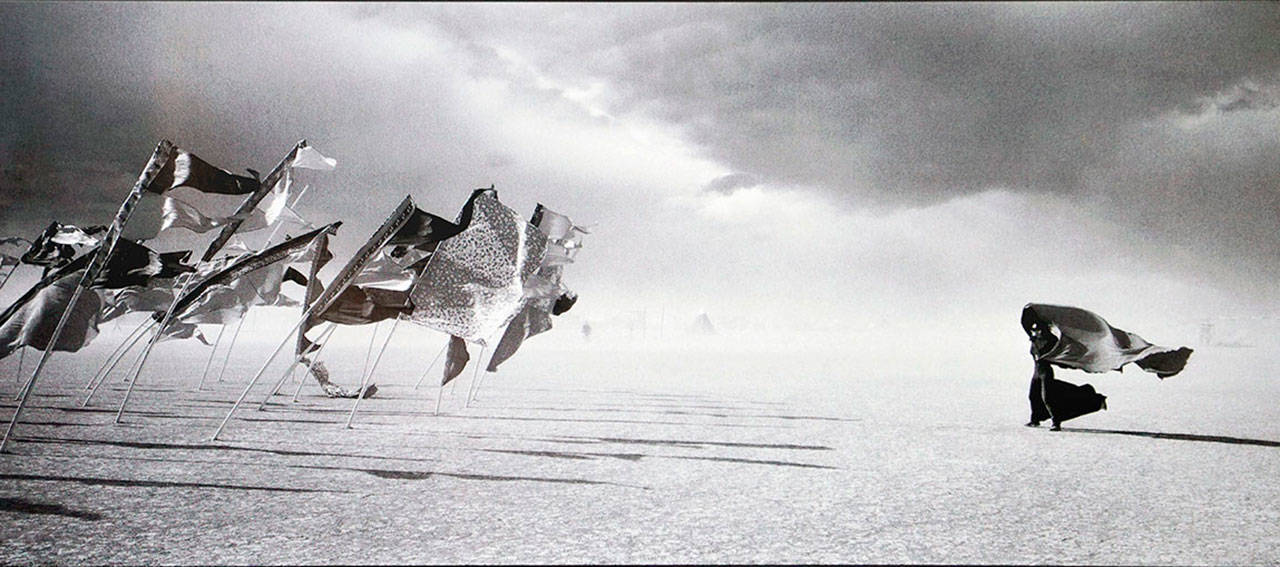

On the book’s cover, Harvey’s black-and-white photo shows a woman before an installation of flags, facing into a dust storm, defiant as the fierce wind whips her free-flowing robes.

“The photo was a natural choice for the cover as it epitomizes the individual spirit at Burning Man,” Harvey said. “It is the individual acts of expression absorbed by the community, with the community enlarged into traditions and rituals and grandiose achievements. It is up to the individuals to make the experience. That’s what distinguishes Burning Man.”

Tickets are available at Vashon Center for the Arts and vashoncenterforthearts.org.