This season of giving also provides a time to be grateful for the gifts we’ve received. Earlier this year, the Vashon-Maury Island Land Trust was given a 9-acre property abutting Judd Creek. It was a complete surprise, just what Land Trust staff wanted and it fit perfectly. The parcel from the estate of Mike Kneeshaw is the latest piece in a mosaic of properties the Land Trust is assembling to protect Judd Creek, Vashon Island’s largest watershed.

Judd Creek flows from its headwaters in Island Center Forest through Paradise Valley and eventually empties out into Quartermaster Harbor. It’s a critical ecosystem that supports several species including our own. It recharges the aquifer that supplies our drinking water and supports populations of cutthroat trout and spawning runs of chum and coho salmon. It’s also the only creek on Vashon that still has the western pearlshell mussel. This freshwater mussel was once the most common species in the Pacific Northwest, but it’s very sensitive to development and dependent on native fish to reproduce. Pearlshell mussel larvae hook onto cutthroat trout and coho salmon to hitch a ride upstream. They drop off and settle into the sandy creek bottom to mature and live out the rest of their lives. According to scientists, pearlshell mussels live an average of 60 to 70 years and can live up to 100 years under the right conditions. As filter feeders, they clean the water they inhabit. Without the fish to transport them upstream, the mussel larvae would be washed out into saltwater and die. So we protect the creek, which protects the fish, which protect the mussels, which clean our water.

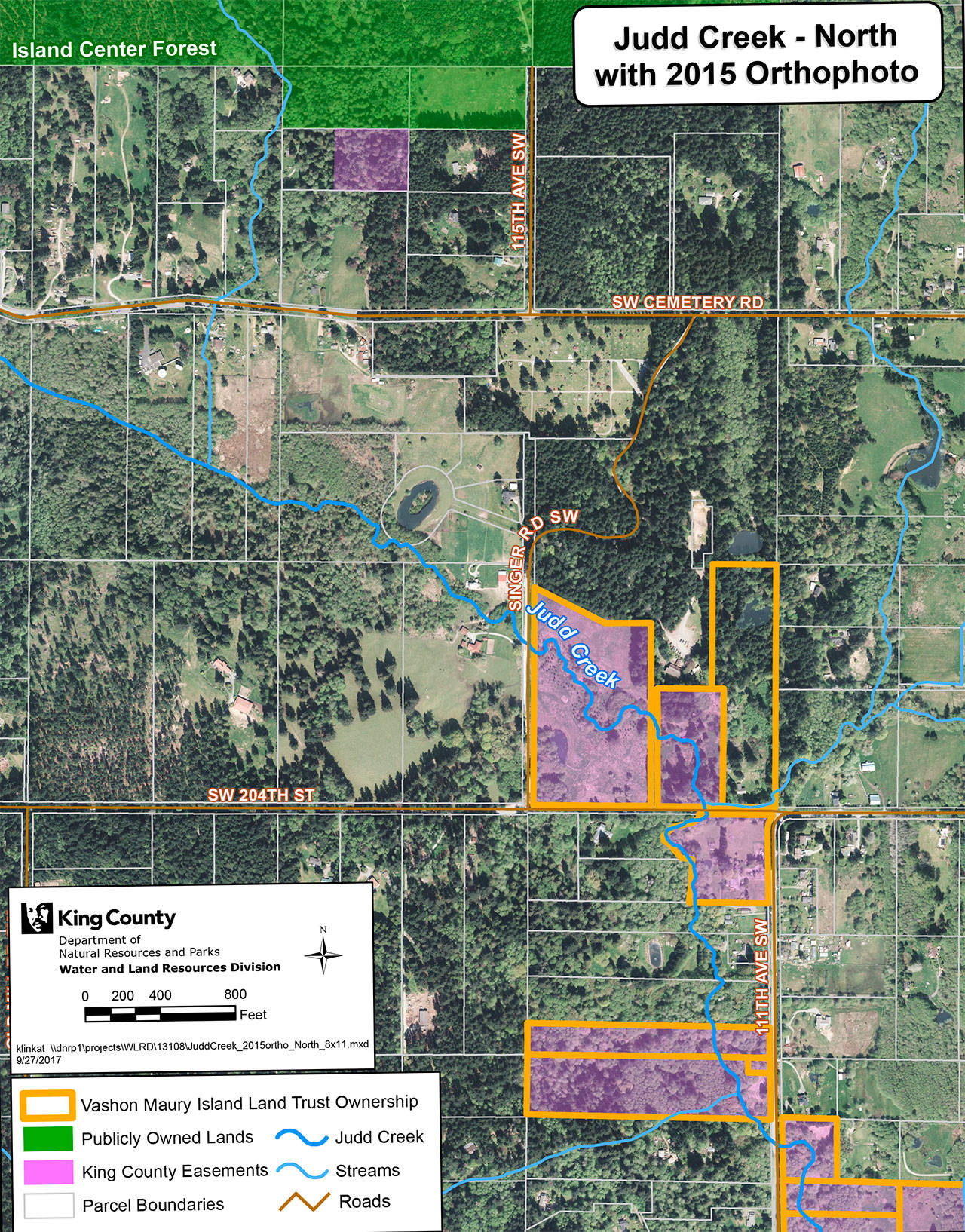

The Land Trust’s mission to protect Judd Creek started 15 years ago with the first purchase in Island Center Forest. A recent flurry of gifts and acquisitions, including the Kneeshaw property and two additional purchases of 14 acres, brings the total for the Judd Creek Preserve to 148 acres. Not all the properties connect yet, but the Land Trust only needs permission from eight landowners along the creek to build a trail from Island Center Forest to Quartermaster Harbor.

Tom Dean, the Land Trust’s executive director, is grateful for the recent land donations to the Judd Creek Preserve.

“Since we started, our donors have really stepped up year after year. Their generous support to our campaigns has enabled us to preserve important habitats and get work done on this critical watershed and others,” he said.

Paradise Valley surrounding Judd Creek was one of the first areas on Vashon cleared by settlers. It has many scars as a result: derelict greenhouses and other structures, junked cars, mechanical debris, as well as broken and inadequate septic systems leeching into the creek. Past logging has left too many aging alders and invasive species and not enough native conifers to shade the creek and provide shelter for spawning salmon.

Land donations are a gift to all of us living on Vashon, but they can be a bit like getting a puppy for Christmas. Puppies are awesome, but they’re a ton of work. Much of the work to restore the land and improve water quality has to be done by big expensive machines. But the rest of it requires volunteers to pick up garbage, remove invasive species, build trails and plant native trees. All of us who benefit from these gifts can show our gratitude and honor those who have donated property by committing to give our time and energy to maintain it.

Vashon Audubon’s Bird of the month

Belted kingfishers can be seen year-round hunting from tree branches or wires hanging over Vashon’s shoreline and freshwater ponds. Their loud rattling call makes them easy to spot in-flight. They often hover above the water before diving in to catch a small fish, which they swallow whole. Kingfishers dig a long tunnel into sandy banks along the water’s edge and deposit their eggs in a chamber at the end of it. According to Ed Swan in “The Birds of Vashon,” kingfishers have nested in the Point Robinson bluffs and along the banks of Shinglemill Creek and Raab’s Lagoon.

In 1758, Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus named these birds Megaceryle alcyon. Ceryle means seabird, and alcyon comes from Halcyone, daughter of the wind god, Aeolus. According to myth, Halcyone was devastated when her husband drowned in a shipwreck. The gods took pity on the couple and turned them into kingfishers. Aeolus then calmed the seas for seven days around the winter solstice so the kingfishers could safely build their nests. This period of calm and peace became known as halcyon days.