Over the past few months, as part of the Black Lives Matter movement and growing recognition of the systematic racism that infuses American society, there are calls to rename historic sites and military bases and to remove statues of Confederate officers and politicians who led the insurrection against the United States that we call the Civil War.

Through his letter to the editor last week, Mark Nassutti brought that question home. Should we rename Maury Island, the second part of the Vashon-Maury Island name, that was named in 1841 by Commodore Wilkes of the American Exploring Expedition to honor Lt. William Lewis Maury who served in the U.S. Navy as part of the expedition? When the Civil War began, Maury resigned his commission and joined the Confederate States Navy. How do we respond to the fact that Maury Island is named for someone who fought against the United States in support of slavery?

William Lewis Maury was born on October 13, 1813, in Virginia, the son of William Grymes Maury and Ann Hoomes Woolfolk, and became a midshipman in 1829. His career as a midshipman and lieutenant was marked by his service in the American Exploring Expedition between 1838 and 1842 where he served on three ships, the Vincennes, Peacock, and Porpoise and was commissioned Lieutenant on February 26, 1841. It was during the Exploring Expedition’s survey of Puget Sound that Commodore Wilkes named Maury Island to honor him. Maury continued in U.S. Navy service serving on the 1854 Perry “gunboat diplomacy” mission to Japan, the Navy Efficiency Board in 1855, and as a member of the Japanese Treaty Commission in 1860.

With the beginning of the Civil War, Maury left the U.S. Navy on April 20, 1861, and on June 10, 1861, was commissioned a Lieutenant in the Confederate States Navy. He made the decision to become a traitor to his country and support a rebellion that had at its root the preservation of slavery. Because all Confederate soldiers were pardoned after the end of the war, they never had to face the true meaning of their treason. They became part of the heroic Southern Myth of “The Lost Cause” and the romantic heroism of State’s Rights when in reality they fought to maintain a system of human bondage that is the dark stain of racism at the core of our national experience.

Maury was initially assigned to a coast defense battery at Sewell’s Point, Virginia. His talent for coastline defense was recognized early on and he was reassigned to the Confederate Torpedo Service. Serving first at Wilmington Station and Charlotte, North Carolina, he was soon transferred to Charleston Station and was then promoted to First Lieutenant in command of the ironclad C.S.S. Tuscaloosa in 1862-63.

While William Maury was serving in Charleston, his distant cousin, renowned astronomer and oceanographer Matthew Fontaine Maury, under the authority of the Confederate States Secretary of the Navy, was dispatched to Europe on a secret mission. Arriving in Liverpool on November 23, 1862, Maury secretly began searching for a vessel that would be suitable for conversion to a Confederate Raider. Utilizing old friendships forged during his service in the U.S. Navy, Matthew Maury was able to purchase the Japan, which was under construction by Denny Brothers in Dumbarton, Scotland. The Japan sailed out of the Clyde River as a merchant’s vessel on April 1, 1863. At a prearranged rendezvous off the coast of Brest, the Japan met with the Alar, a small merchant vessel that was carrying arms and ammunition to outfit the Japan as a raider, as well as the Captain William Lewis Maury. After much labor, Commander William Lewis Maury transformed the Japan into a Confederate Cruiser and rechristened her the C.S.S. Georgia.

C.S.S. Georgia was a screw-steamer with sail auxiliary, and five mounted guns: two 100 pounders, two 24 pounders, and one 32 pounder. Leaving the coast of France on the 9th of April 1863, the Georgia cruised the North and South Atlantic in search of United States vessels, capturing or destroying $431,270.00 worth of U.S. shipping over the next seven months. After taking numerous prizes, the iron-hull Georgia was in need of maintenance. Cherbourg, France was a welcome harbor when the Georgia arrived on October 28, 1863. Though officially neutral, the people of Cherbourg welcomed the Confederate Raiders as celebrities. The Georgia’s Captain, William Maury, had been ill since leaving the Cape of Good Hope in late August; he had also learned that his family had become refugees. The Georgia remained in Cherbourg for the next several months while being refitted. On January 19, 1864, Maury was relieved of his command at his own request, citing his continued ill-health.

After the war, Maury was in Richmond, Virginia, and met with General Robert E. Lee to discuss repatriation of former Confederate officers. Maury had difficulty finding a position; he eventually secured a job as a customs collector in New York. He died on November 27, 1878.

On July 1, 2020, the mayor of Richmond, Virginia, ordered the removal of Matthew Maury’s statue on Richmond’s Monument Avenue, along with memorials to other Confederate leaders. Matthew Maury’s statue was taken down the following day, and by July 9, a total of 11 Confederate symbols had been removed. (Protestors toppled the statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis in June, also on Richmond’s Monument Avenue.)

Should we topple the name Maury from our islands and find another name for Maury Island? Or, do we do like King County, and rename Maury Island after a different Maury who does not carry the legacy of rebellion and support of slavery? Or, do we leave the name as it is and recognize the tarnished legacy William L. Maury’s name carries with it?

Whatever you think we should do, we first need to build a community census about what is the appropriate action. We also need to recognize that any change, whatever it may be, needs to go through the approval process set up by the Washington State Board on Geographical Names, which could take up to two years. Perhaps the newly emerging Vashon-Maury Island Community Council is a good place to begin these discussions.

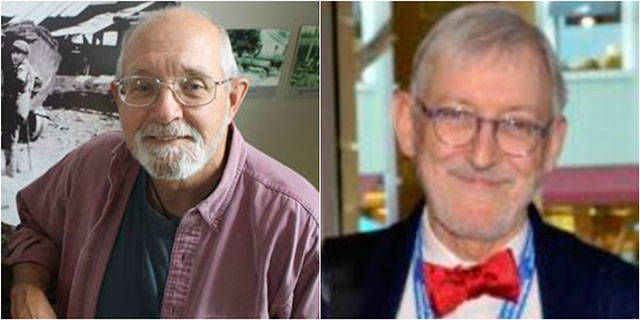

Bruce Haulman is an island historian. Steven C. Macdonald is a retired epidemiologist and a 20-year resident of Vashon Island.