After training in Puget Sound for months, a relay swim team from Vashon crossed the English Channel in 17 hours and 29 minutes, with islander Randy Perkins completing the final stretch just after midnight on July 13. He reached a sandbank in shallow, dark water off the coast of France and retrieved a collection of rocks from the shore to share with his teammates, a small gesture symbolizing their achievement.

Overjoyed, islander Heidi Skrzypek waded back into the channel herself once the shoreline was in sight.

“We were swatting jellyfish in pitch black water, and there was phosphorescence in the water,” she said by telephone from France, describing the soft glow of bioluminescent plankton in the waves as if guiding them to land. “It just was like, ‘Ahh, we’re finally here!’”

Before the relay team departed for England, their confidence was high. Looking back, their intensive regimen was pivotal to their success.

“Training on Vashon in all that cold water and the current was such good preparation,” said Skrzypek, adding that she felt exhilarated to have completed the swim. “I’m happy to be alive because I thought I was going to have a heart attack and die,” she said. “It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

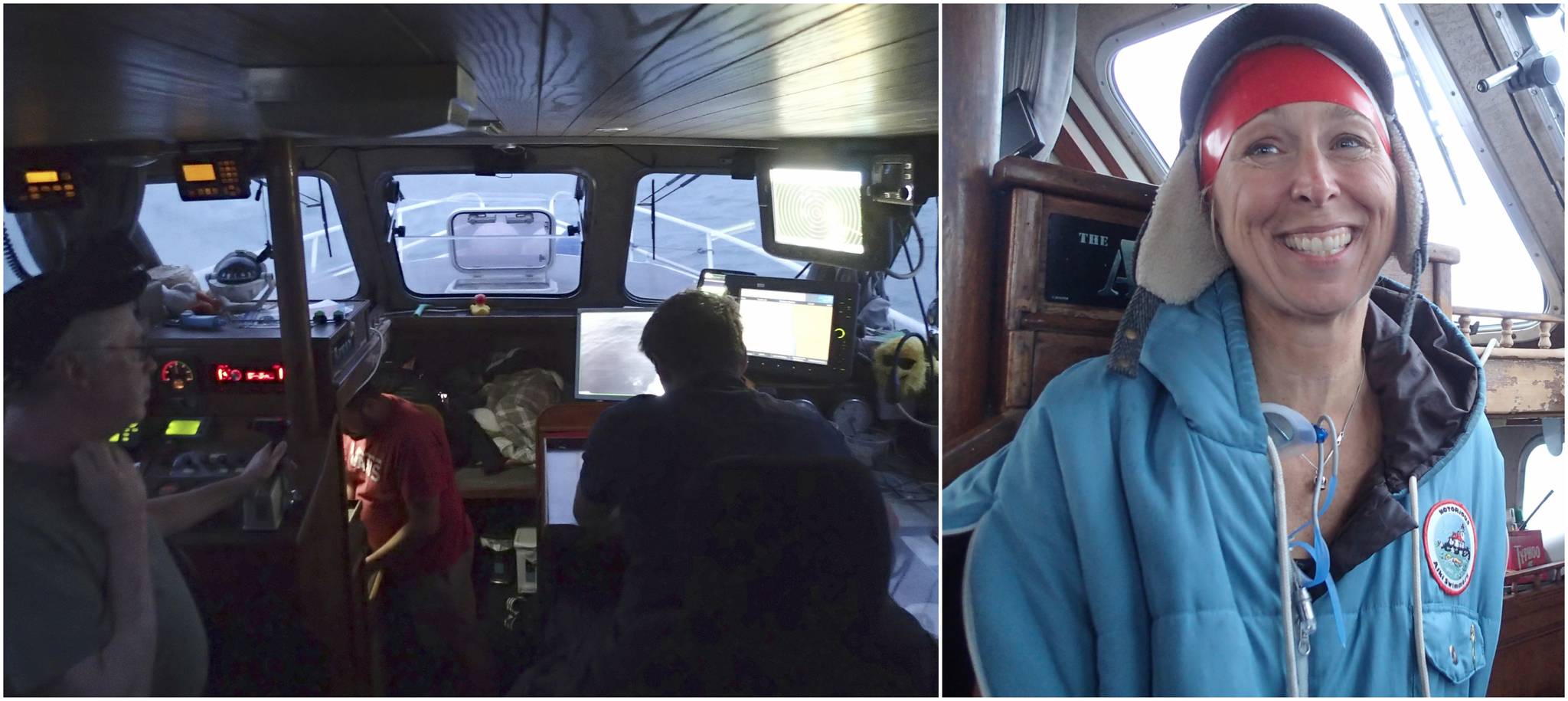

The relay team, consisting of Skrzypek, Perkins, Kate Curtis and Curtis Vredenburg, departed from Folkestone, England, just before 6 a.m. on July 12 on board the support vessel Sea Satin, with pilot Lance Oram. Each member of the team swam an hour at a time in the channel, which was unseasonably warm at 18 degrees Celsius — about 64 degrees Fahrenheit — though conditions were rough, and the day overcast. They encountered numerous jellyfish; Skrzypek was shocked by how many were in the water. Compass jellies plagued Curtis, yet she swam in what Skrzypek said was “pretty much the worst part of it,” battling choppy seas in an area near France.

“This was a beast,” said Curtis. “The channel, in one word, is a beast.”

Skrzypek said that frustration mounted as their approach to France was beset by the tide dragging them farther south, so that they made no meaningful progress. She credited the boat pilots for their ability to navigate the swift currents, helping the team get ahead.

“You have to keep going,” she said. “The nasty part before you get to France is known to be the most difficult part of the swim. Basically, with the four of us, we had to take turns to get dry, get warm, get fed and shiver out.”

Each member of the team had three hours to complete those essential tasks while minding the ongoing swim. Curtis noted that it sounds like more time than it felt.

“Now we know a four-person relay is pretty hard,” said Skrzypek. “It takes several hours to shiver out. It’s get out, dry off, peel off wet clothes, re-dress and shiver, shiver, shiver; get hot liquids, eat (food) fuel and help your teammates. It was really quick.”

Their team, the Puget Sound Swimmers, crossed the channel in part to benefit People For Puget Sound, a program of the Washington Environmental Council that seeks to protect the vulnerable waters and habitats of the Pacific Northwest.

“We were the only boat that actually crossed that day, and that’s a testament,” said Skrzypek, recounting the final hours of their crossing. Sometime after 9 p.m. and with 3.25 miles to go, she could see the lights of France. “The fact that we went out on kind of a gnarly day is a testament to the confidence our captain had [in us], and to our swimming, just so we could get it done — and we got it done, which is very cool.”