Kajira Wyn Berry hoped that posting haiku on three signs, Burma-Shave style, at the bottom of the north-end ferry hill would slow down drivers. The drivers haven’t slowed down, but Berry’s beautiful calligraphy of haiku written by Island poets has become a landmark.

When the haiku was repeatedly stolen earlier this year, she learned how much Islanders value the poems.

“I can’t tell you how many dozens of people would stop me on the street and say, ‘Oh, would you please bring them back, we really love them.’”

She also received donations for materials, and the poems are currently back up. Berry reflected, “This is so touching, because it tells me the community now considers that their own.”

An Island resident since 1975, Berry co-founded the Vashon Allied Arts (VAA) and the Vashon Island Kayak Company while pursuing her own varied creative life. Born in New York State in 1927, Berry was raised in New England, attended college in Portland, taught school and worked for many years as a photojournalist. She continues to write, paint and sometimes sculpt.

“When I’m writing, I’m not painting; when I’m painting, I’m not writing. I think they’re all fed by the same river that flows through me all the time.”

Calligraphy holds a special place in Berry’s work. She’s taught the art to children and adults, including more than a hundred students on Vashon. She learned calligraphy from Lloyd Reynolds, who taught for 40 years at Reed College in Portland. Berry came to Reed to study with him, and he was a major influence on her and on many others. After her graduation, she taught with Reynolds for several years.

“The Sufis say that at any one time in the world there are seven great teachers, but they may not know they are great. Lloyd was like that. He was a great scholar; he taught art, graphic art, calligraphy, humanities, Eastern religions.”

Berry’s expressive face lit up as she recalled Reynolds’ classes and the friendships she formed with artists and poets, including Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen. After graduating from Reed in 1956, Berry worked for the college, writing and photographing stories for its publications. She went on to teach at an independent school in Portland, where she developed a curriculum in italic handwriting. In summer, she crossed the country with her three children and then-husband Don Berry.

“We used to load up the VW bus and take a different route every summer. We explored every park and every historic monument. The kids loved to travel — we were great wanderers.”

Berry’s love for adventure served her well when she left teaching and focused on work as an independent photojournalist. “I found I liked taking pictures better than writing stories. I got to live lots of different lives with great intensity: a day with a college president, a day in a tattoo parlor, on the political trail with Al Gore. You watch, you wait, you take the pictures.”

She also worked as a television news reporter in Portland for NBC and took on a variety of freelance writing projects. After her kids were grown, Berry’s curiosity led to wider travels. She cruised in the Caribbean with her husband for over a year. They left their boat in a hurricane hole in Antigua, and when it was pirated — stolen — they were “adrift.”

“We were footloose and fancy free. A friend asked us to come up to Vashon and look after her kids, and after six weeks we fell in love with the Island, bought a boat and lived aboard for a year in Dockton.”

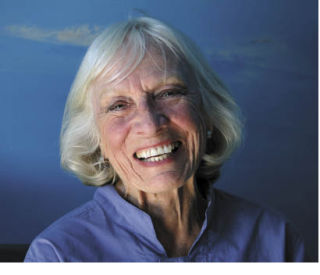

Today, Berry lives in a comfortable older home in Burton, full of paintings, art and books. French doors in her working studio open to a wide expanse of green hillside. The sky-blue walls, painted with scattered white clouds, brought out the luminous blue of her eyes as she talked about the many turns in her long creative life. She recently published her first novel, “Everlasting Sky,” which grew out of decades of research and a personal connection with her subject, the Chinese Empress Wu Chao.

The author’s note to the novel, posted on

Berry’s Web site, describes how she first encountered Wu in 1968, while viewing a friend’s painting. “I was inside the painting, myself as a different person, walking across a vast and lovely garden, experiencing sights and sounds quite foreign to me … The next day I went to the library and looked up these clues of images and a few words. There they were — the architecture, music, names … a history and culture that I had never studied or read about before.”

This unusual experience led to “Everlasting Sky,” which uncovers Wu Chao’s life, from 618 to 705, and her peaceful and prosperous reign.

“She was really an extraordinary ruler,” Berry said. “She angered the Confucians greatly. She enlarged the system of canals so there could be instant communication throughout the kingdom. She helped rewrite women’s rights in China. People from all over the planet flooded through there for education, for trade, for ideas. It was really a yeasty time.”

The novel developed over nearly four decades, and Berry set it aside several times. But she kept hearing Wu Chao’s voice saying, “Finish the book. I want my voice heard.” Completing this long novel seems to have been a personal triumph for Berry.

“I recently took all the completed manuscripts from the last 20 years to be recycled. It was quite a little celebration, watching them all go down that chute!”

As Vashon nurtured Berry’s creative pursuits, she helped weave together the arts community. When VAA was first established, Berry wrote a series of articles for The Beachcomber, and she credited former editor Jay Becker with encouraging a growing awareness of Vashon as a place for artists.

“The Beachcomber gave people who lived here a sense of what was happening in the arts, but it also went off Island, when people were wondering if this would be a good place to live. People said ‘Hey, where there are a lot of artists is a good place to raise kids.’ So it was a self-fulfilling prophecy: it generated the interest in the kind of people who would make the arts flourish here.”

Today, Kaj Berry is contemplating what to do with a studio full of completed works and working on a new novel, set on the Oregon coast in 1968. She’s a regular at the monthly “Mondays at 3” haiku group. She continues to travel globally, with her beloved companion David Steel. At home, she appreciates Vashon’s community spirit, where “neighbors know neighbors.”

“In New England, there was room for oddities, odd people and odd endeavors. I love that about Vashon. There is generally a ‘live and let live’ joyousness between people here – because we also share the good parts.”

Berry’s “good parts” include kayaking. While she’s paddled in Bali, Burma and Guatemala, she reserves her highest praise for the waters around Vashon.

“Puget Sound is the world’s greatest kayaking, because it has all these little places you can get into. And the wildlife is just spectacular.”

It’s fitting that a recent Highway Haiku, written and calligraphed by Berry, describes the sea kayaks in her own back yard.

Six sea kayaks

sleep spooned together

waiting for summer

The public poem embodies her passions — for calligraphy, for poetry, for kayaking, for Vashon — and for the creative spirit she brings to all she does.

— Margot Boyer is a freelance writer living on Vashon.