An effort aimed at building relationships between the Puyallup Tribe and the Vashon community has now resulted in visible signage, honoring the First Peoples of Vashon, the sx̌ʷəbabš (Swift Water People), which will soon be distributed free of charge to islanders.

The signage — lightweight yard signs — have been produced thanks to the efforts of a local group, working in partnership with the Puyallup Indian Tribe and Puyallup artist Daniel Baptista.

Rayna Holtz, a member of the local group, praised Baptista for his work and credited Amber Hayward, head of the Puyallup Language Program, for her work in identifying Baptista as the project’s artist and advising the group in other significant ways.

The yard signs, paid for by a King County Alan Painter grant, will be given to islanders free of charge from 5 to 8 p.m. Friday, March 3, at the Vashon Heritage Museum. The museum will also continue to offer the signs during its regular hours in the following weeks, as long as supplies last.

According to Holtz, the idea for the signs came from meetings, held over the course of the past year, attended by members of the Backbone Campaign, Vashon-Maury Island Land Trust, Vashon Island Unitarian Fellowship, the Natural History Museum, Vashon Heritage Museum, Vashon Island School District and other organizations.

“Recognizing that [spoken] land acknowledgments are a first step, [we] looked for actions to bring better balance and reciprocity to [our] community’s relations with the First Peoples of this place,” she said.

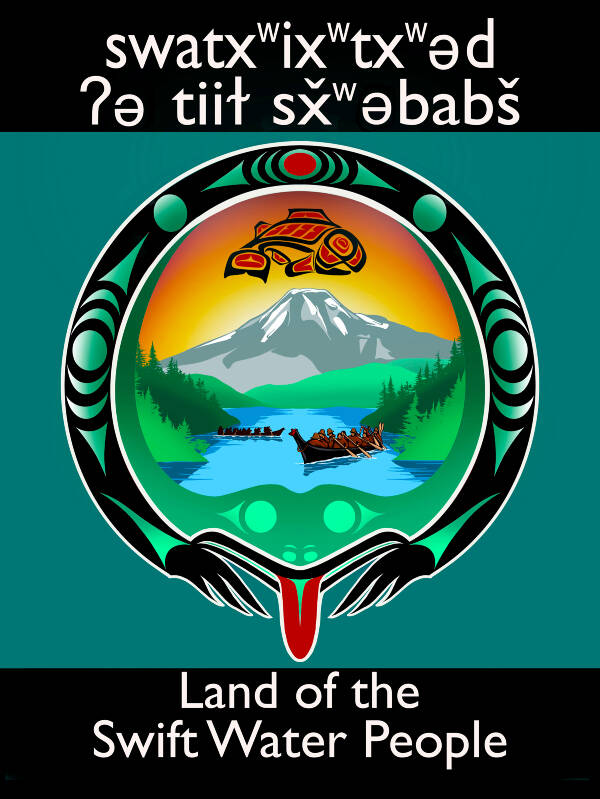

At the center of Baptista’s richly colored image, on the signs, are Native people paddling two traditional cedar canoes across Puget Sound, surrounded by forested hills.

The location is identified by a name written in Twulshootseed, the language spoken by tribes living around the Puget Sound area in Washington state, and the scene’s frame is formed by the body of a bright green frog whose tongue points to the translation “Land of the Swift Water People” at the bottom.

According to Holtz, it is fitting that these signs have emerged during February, known as the season “When Frog Croaks” in Puyallup seasonal references.

“Soon the evening choruses of tree frogs will begin to announce a new year of growth, and Baptista’s design is part of a new growth of awareness and reciprocity between current islanders and the Puyallup Tribe of Indians,” she said.

Tom Dean, of Vashon-Maury Island Land Trust, described his hopes for the new signage in a different way.

“One of our goals is to make Vashon a more welcoming place for the descendants of the original inhabitants,” he said. “We hope to raise awareness amongst islanders of the continued presence of Puyallup tribal members in their homelands.”

Asked for a statement about the project, artist Daniel Baptista replied in Twulshootseed with a translation: “txʷəl gʷəlapu, gʷəlapu dʔiišəd, dsyayayəʔ. Daniel Baptista ti dsdaʔ, spuyaləpabš čəd. “ʔəshiiɫ čəd ʔə ti dsuhuyšid ti tačuʔ ʔə ti sx̌al. To all of you, all of you are my beloved people, my relations. My name is Daniel Baptista and I am a Puyallup tribal member. I’m happy to have made this sign for Vashon Island.”

Oral history, archaeological evidence, and tribal and academic research show that a band of Coast Salish people known as the sx̌ʷəbabš occupied numerous villages in Quartermaster Harbor as well as Gig Harbor and Wollochet Bay as long ago as the end of the last ice age or earlier.

After the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek and the subsequent war, the sx̌ʷəbabš were forcibly displaced to the Puyallup Reservation and several others reservations.

What non-native people know of the history of the First Peoples of the South Sound has been fragmentary and scattered for most of the past two centuries, Holtz said.

Most early written records were brief journal entries from shipboard explorers, observations by employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Nisqually, journals and letters of early settlers such as Ezra Meeker, records from missionaries such as Myron Eels, and inaccurate reports by government officials.

Some direct narratives of Lucy Gerand, a sx̌ʷəbabš woman born in Quartermaster Harbor, were collected by anthropologist Thomas T. Waterman in 1918, and later others were recorded in hearings of the 1927 U.S. Court of Claims, but these were long buried in research collections and legal libraries.

They are extremely valuable, said Holtz, because they directly identify longhouses and village sites, native names for many places on Vashon-Maury Island, and various practices associated with plant cultivation, longhouse building, and more.

“Much of Native history and culture has been passed down orally by Native people in secret, while the U.S. government attempted to eradicate their language and culture,” she said. “Many traditional ceremonies and other practices were outlawed, and mandatory boarding schools forbade the children to speak their Native languages.”

Vashon 101 talks detail more history

The Heritage Museum’s “Vashon 101” webinar speaker series will soon offer two opportunities to learn more about the Native Peoples of Vashon directly from members of the Puyallup Tribe.

Binah McCloud, Puyallup Director of Student Success and Culture at Chief Leschi School, will speak at 7 p.m. Thursday, March 9, via Zoom.

McCloud’s family participated in the Fishing War of the 1960s-70, and she will describe the historic struggle that won them decisive recognition of their treaty fishing rights.

At 7 p.m. on Thursday, May 11, Vashon 101 attendees will hear from Brandon Reynon, the Puyallup Tribe’s Director of Tribal Historic Preservation, who will give an overview of the sx̌ʷəbabš people.

Register to receive Zoom links to the talks, and find additional information about the yard signs and the culture and history of the sx̌ʷəbabš and Puyallup people at vashonheritagemuseum.org.

Correction: As originally published both online and in the print edition of The Beachcomber, this article originally omitted Vashon Island School District from a list of collaborating organizations that had helped develop and advocate for the signage. We regret the error.