Frank Abe was in college when he began to realize that the tens of thousands of Japanese Americans who were sent to “relocation camps” with nice-sounding names — Heart Mountain, Tule Lake, Topaz — had been held in what he now calls “America’s first concentration camps.”

As he dug deeper, he made another discovery: that the story of their passive resignation to widespread wartime incarceration was also a myth. In fact, as he eventually learned, thousands were part of an orchestrated resistance to this captivity. Others refused to sign confusing and ill-conceived loyalty oaths because of how they were being treated. People were beaten, tortured, imprisoned.

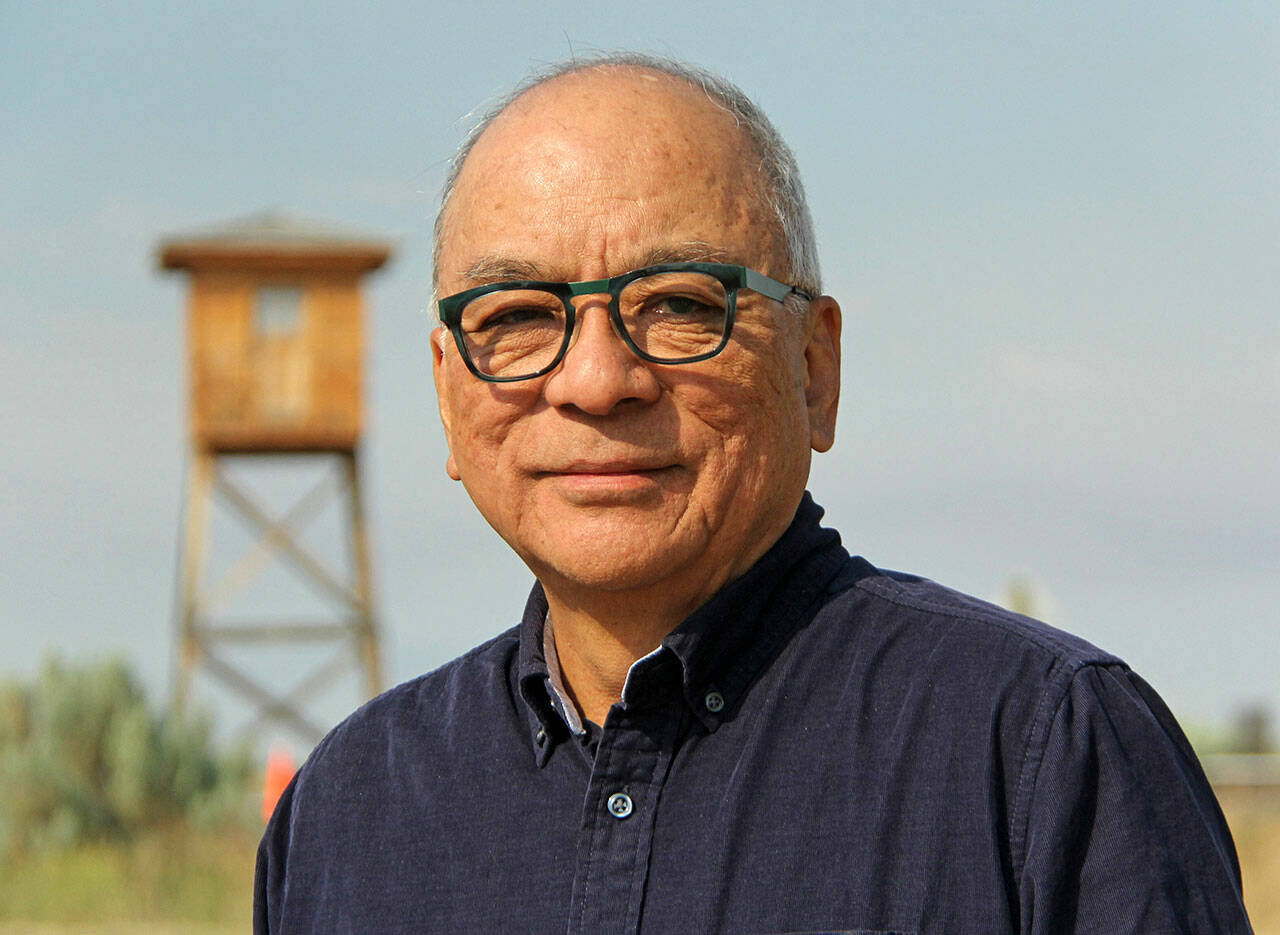

Abe, angry that he had been misled and fascinated by this new narrative, made it his mission to tell the fuller story of the Japanese American response to their wartime incarceration.

And on Feb. 19 — the 80th anniversary of the executive order that forced the removal and incarceration of 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent during World War II — he’ll bring that story to Vashon.

In an event hosted by Mukai Farm & Garden, Abe and Tamiko Nimura will discuss their new graphic novel, “We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Incarceration,” a powerful, historically accurate look at three individuals who, in different ways, stood up to their captors.

The history is deeply relevant to Vashon Island. In 1942, 111 people were given two days’ notice to show up at Ober Park, where they were herded onto trucks and sent to an assembly center in California. Many ended up in one of the camps at the heart of the graphic novel — Tule Lake, in north-central California — infamous because it was reclassified in 1943 as a high-security “segregation center” used to punish thousands of people who resisted incarceration.

And of course, Abe points out, the story is relevant to anyone who cares about race relations today. The 120,000 people forced into these camps were targeted solely because of their race, “and race is still dividing us today,” Abe said. The book opens with the FBI “knocking on the door to arrest our grandparents,” he said. “It ends with ICE agents breaking down the door to deport unwanted immigrants. The take-away is that some things haven’t changed.”

Tina Shattuck, executive director of Mukai Farm & Garden, said the organization invited Abe and Nimura to speak in part because of the book’s far-reaching meaning — the way people have been “othered” for centuries. “We want to acknowledge and recognize the anniversary of this very important day. It’s also an opportunity to … make sure it never happens again.”

Abe, 70, is a third-generation Japanese American whose father was incarcerated at Heart Mountain in Wyoming. But his father was a boy during that time; a quiet man, he never spoke of it. Like so many members of his community, Abe said, his parents (his mother, also a U.S. citizen, was in Japan during the war) wanted to put this chapter behind them and reclaim their lives as Americans.

But as a young man, Abe began to wonder why they didn’t resist what was clearly a wholesale deprivation of their civil liberties, and he began to hear from his parents’ friends — women in his mother’s singing group, gardeners who worked with his father — that many did fight their imprisonment.

Abe, who later became a reporter for KIRO Radio, began interviewing survivors of the camps, writing about what he learned. His investigation, he said, was both illuminating and upsetting. The stories of resistance were not simply ignored but actively suppressed, he said. “My parents’ generation embraced the idea of being the good minority, and the idea of … resistance did not fit that narrative.”

As he spoke, he held up a book, “Nisei: The Quiet Americans,” one of the few popular histories about Japanese Americans in the early 1970s. “It’s fair to say I was outraged in reading this. … It was not any kind of legacy that I, as a third-generation, a Sansei, wanted to have — that of quietly cooperating with the government. … This book fueled my quest to reframe our history.”

And reframe he did.

Abe helped to produce the first-ever “Day of Remembrance” in 1978 — a gathering of thousands of people at the former Sick’s Stadium, in Seattle, to begin the campaign to redress Japanese Americans for their incarceration. The Day of Remembrance is now a nationwide event hosted by the Smithsonian on Feb. 19, the date that President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066.

He wrote and directed a one-hour film, “Conscience and the Constitution,” that told the little-known story of organized draft resistance at Heart Mountain — a story of people resisting not because they were anti-war or anti-American but because they could not fight for a government that denied them their rights as citizens. It was distributed nationwide on PBS in 2000.

He edited, with two others, “John Okada: The Life and Rediscovered Work of the Author of No-No Boy,” a look at the man who wrote a novel about a Japanese American who refused to fight for a country that imprisoned him. Okada’s novel — like the No-No boys themselves — was initially rejected and ignored. Abe and his co-authors’ meticulous look at his life and works won an American Book Award.

He did all this as he was also developing his career as a journalist and communications professional. After 14 years at KIRO, he worked as a communications director for King County Executives Gary Locke and Dow Constantine until his retirement in 2019.

Abe decided to work with Nimura and two artists — Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki — on a graphic novel after the Wing Luke Museum put out a call for such a book and the four teamed up to submit a proposal. “I never planned to be a graphic novelist,” Abe said with a smile. The book was published by Chin Music Press in Seattle last spring. It’s now in its third printing.

But as Abe discovered, the format is a powerful and moving way to tell three different stories, woven together as a compelling narrative of resistance.

Jim Akutsu, the inspiration for Okada’s novel “No-No Boy,” was one of the young men who refused to be drafted. Labeled a draft dodger after the war, he experiences a tragedy as a result of his stance. Hiroshi Kashiwagi, imprisoned at Tule Lake, refuses to sign the loyalty oath, renouncing his U.S. citizenship in the process. And Mitsuye Endo is both a reluctant hero and remarkably brave; imprisoned at Topaz, she refuses a chance at freedom so that her history-making civil suit could reach the U.S. Supreme Court and hasten the closure of the camps.

Abe notes that the suppression of uncomfortable truths is hardly new in America. “In our nation today, we’re seeing a concerted attack on critical race theory, which in fact is nothing more than an attack on the teaching of history,” he said.

“This history of Japanese American incarceration falls squarely in that realm of American history that has been ignored or suppressed,” he said. “I’m pleased that our book has found its audience.”

Mukai Farm & Garden will commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Day of Remembrance with an online discussion with Frank Abe and Tamiko Nimura, authors of “We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration,” at 4 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 19.

Register for the talk at tinyurl.com/bdfd4uvc and find out more at mukaifarmandgarden.org. The event is free, with donations gratefully accepted.

Correction: A previous version of this story contained a misspelling of Mitsuye Endo’s name. We regret the error.