Nathan Dorn, Jr., an islander who was known and beloved by many on Vashon, died on Monday, April 4, when he was fatally struck by a hit-and-run driver in an accident that occurred just south of the Harbor School on Vashon Highway S.W.

A Vashon man, Michael Irwin Henderson, was arrested on April 8, and charged on April 12 in connection with Dorn’s death. Henderson faces two felony charges of vehicular homicide and hit and run. Charging documents cited evidence provided by Vashon community members who suspected Henderson of the crime.

The state, detailing multiple past DUIs and other driving charges against Henderson, has requested bail be set at $100,000, with numerous stipulations including a recommendation for release to electronic home detention, saying “the defendant is a flight risk” and “a grave danger to the community.”

Henderson has had an active bench warrant since 2018 in connection with a charge of DUI in Ruston and several other cases of failure to appear in court. His next court date is his arraignment scheduled for 8:30 a.m. Monday, April 25 in room E1201A of the King County Courthouse.

Dorn, who had been walking home on the wide shoulder of the highway on the evening of April 4, died of multiple blunt force injuries, according to the King County Medical Examiner’s office.

Islander Jesse Whitford was the first on the scene to where Dorn was found. Whitford had been coming off the 10:35 p.m. ferry from Fauntleroy and was traveling southbound on Vashon Highway. As Whitford was driving, he said he saw something that “didn’t feel right” on the side of the road and turned around to see what was there. At about 11 p.m., Whitford found Dorn’s body and made the initial call to 911.

According to Whitford, the Sheriff’s department responded in less than five minutes, with EMTs following soon after. Whitford remained on the scene for more than an hour and gave a statement once detectives were able to arrive on the scene. Whitford did not depart the scene until around 12:20 a.m.

He also reported that Dorn had been wearing a bright yellow reflective vest at the time — a safety measure that many other islanders confirmed Dorn always took while walking the highway or even waiting for the bus.

In the wake of Dorn’s death, many islanders expressed an outpouring of grief over the death of a man they described as generous, kind and gentle, with a witty and sometimes ribald sense of humor.

He was easily recognizable about town in his uniform of bib overalls, worn with a button-down shirt, sturdy boots and a wide-brimmed hat.

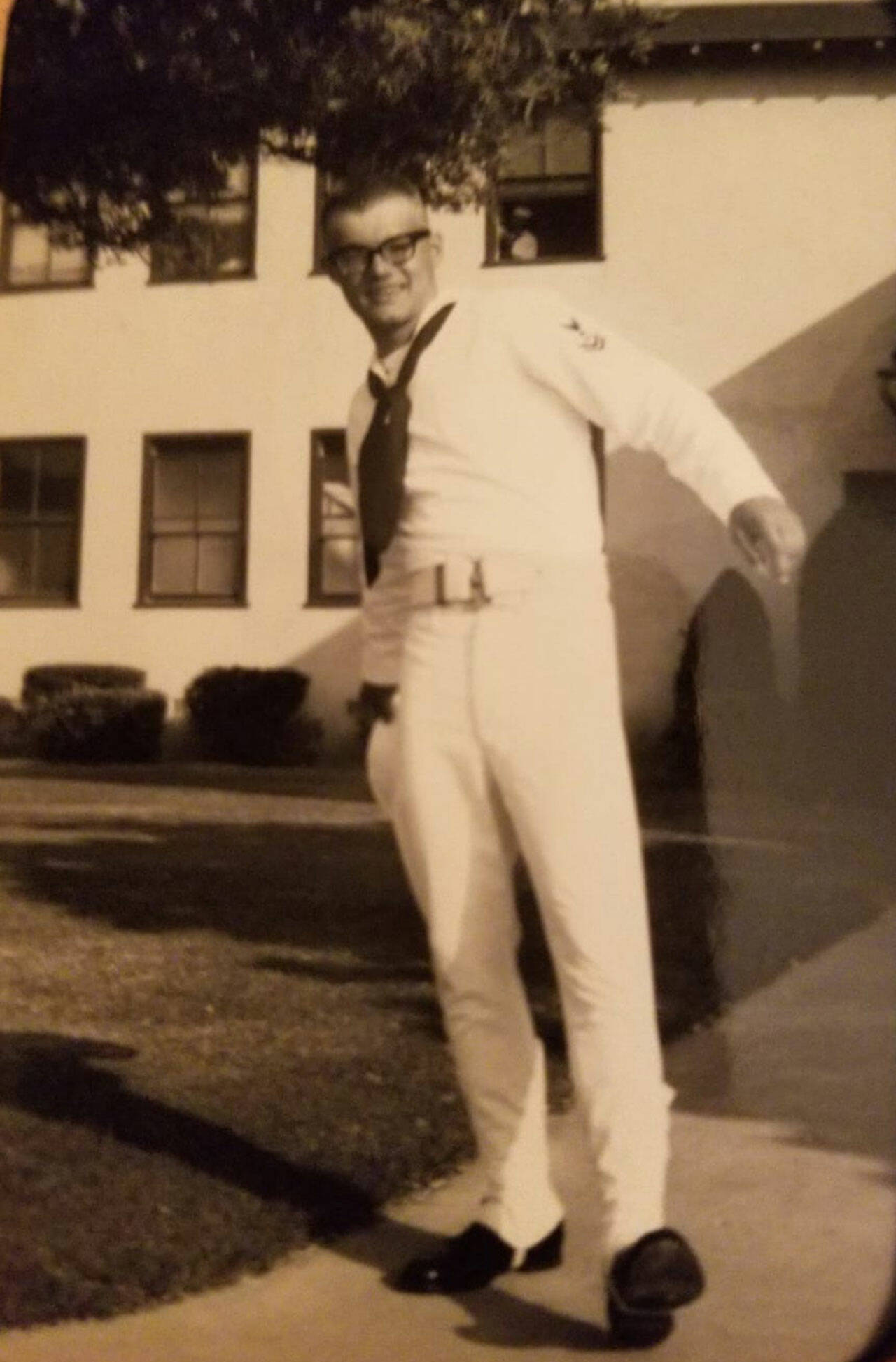

Dorn, a decorated Vietnam veteran, was born on Oct. 15, 1947, in Wenatchee, the second-oldest in a family of five children born to Nathan and Dolores Dorn. His father, while serving in the U.S. Navy, had participated in the Normandy Invasion in World War II; his grandfather had been badly injured and mentally traumatized by his service in the U.S. Army during World War I.

Nathan’s early years were spent in Wenatchee, and then in West Seattle, where the family moved.

Nathan joined the Navy at the age of 17, said his sister, Dorinda Kopp.

In Vietnam, Nathan served as a Navy Hospital Corpsman, often coming under fire as he worked as a medic on battlefields while attached to a platoon of Marines. There, his sister said, he saved lives but had been deeply scarred by his experiences. Nathan was badly injured in the war, and granted full disability, she said.

After his recovery from most of his physical injuries, Nathan returned to Seattle, where he was married, and became the father of two daughters.

When the marriage ended, after only a few years, Nathan moved to Vashon, to live simply on a five-acre plot of land he had purchased after returning stateside. His home for most of the decades he lived on Vashon was a modest travel trailer.

In that simple abode, said his daughter, Heather Craft, her father was a devoted and patient parent to her and her sister on weekends, summer holidays, and whenever else he could spend time with them. He delighted in taking them on nature walks, she said, exploring the nooks and crannies of the woods around his property and beyond.

He was an avid mushroom hunter, his daughter said, and loved bumblebees so much that he planted flowers and plants all around his property, to draw more bees. His love of bees, she recalled with a laugh, was so strong that he once bought both his daughters and himself matching yellow and black-striped sweatshirts so that they could all walk around together, looking like bumblebees — a memory Craft now delights in, but recalls as being somewhat embarrassing at the time.

“He was gentle and kind all my life,” she said, adding that later in life, he showed the same loving care and delight in his grandchildren, preparing them delicious meals they loved, made from unusual ingredients such as artichokes and chicken gizzards.

Throughout his life, both his sister and daughter said, Nathan had wrestled with lingering demons from his time in Vietnam — though his battles were always focused inward, rather than outwardly expressed.

Both Kopp and Craft said he was deeply disturbed by sounds, including fireworks, that caused his mind to return to the war.

“If a helicopter went over, you would see this look in his eyes, and he’d have to get up and walk through the woods,” said Craft.

Nathan had been awarded three medals for his service, including a Purple Heart and Bronze Star, his sister said, but had discarded two of them and refused another. Craft said she had seen her father’s Purple Heart medal, but he took no pride in it — saying that the only reason he had it was because other people were hurt.

“He would have rather had the people,” she said.

And yet, despite Nathan’s physical and mental scars from the war, he lived a rich life on Vashon, filled with quiet service to others.

“I truly feel his time in Vietnam made him even more of a protector and gentle soul,” his daughter said. “He was somehow always able to help people and love them where they were and not judge them … I’ve spoken with people who said he saved their lives.”

She also described her father as a voracious, daily reader, who connected with others who shared his love of books.

But she also laughed as she recounted her father’s sometimes off-color brand of humor, saying he had always told her that when he died, he wanted to be buried under a walnut tree, so that “people can go there and eat my nuts.”

Now, she said, she planned to honor that request, through a green burial process that would turn his body into soil, into which she would plant a walnut tree.

Kopp also recalled his singular sense of humor and how he had retained the same mischievous traits he had shown as a child in Wenatchee. His laugh, she said, was infectious.

Shawna Boudin, who works at Sporty’s, said that Nathan was a daily customer who often held court at a table by the front window of the establishment. She agreed about Nathan’s laugh, which she described as an “almost maniacal giggle” that was also extremely loud. Many times, she said, she had told him to keep it down, she recalled with a smile. But, like many others who knew him well, she described him as a “gregarious, really smart and generous man” who helped others in hard circumstances.

Amber Guthrie, who grew up on Vashon, was one of the people Nathan helped — offering her a place to stay and buying her clothes when, due to problems in her home, she was homeless for a time during her teenage years.

“He was an amazing human being,” Guthrie said, recalling how Nathan had been a non-judgemental and supportive presence during those troubled years.

In a social media post, Susan Pitiger recalled how she had only met Nathan once, on a memorable occasion — a memorial of the life of her late son, Justin, on Justin’s birthday. “When he found out why we were celebrating, he went to the ATM and brought us $100 for Justin’s scholarship fund,” Pitiger wrote.

Others described interactions with Dorn that had left lasting impressions.

Islander Jason Priest recalled how, after just moving to the island, he had shared a driveway with Dorn. He said that after he shared his own background as a United States Marine Corps infantryman with Nathan, his neighbor had opened up to him about his own military service and its lingering impacts on his life.

“He saw things nobody should see. He saved the lives of Marines, “said Priest. “He was and is a real hero. I know he held the conviction of ‘no man left behind,’ which makes what happened to him all the more maddening.”

But many other islanders described more lighthearted interactions with Nathan that included convivial banter laced with jokes and kindness.

“I called him grandpa, as he and I would share conversation about our granddaughters whenever and wherever we would cross paths — him in his broad-brimmed oil-soaked hat and huge grin ready to bust into a smile whenever he hit the opportunity,” said islander William Rowe, in a Facebook post.

His daughter said that these kinds of friendly, day-brightening interactions were a part of her father’s life for a reason. She recalled something her father had told her.

“Sometimes I’m down and out, but if I can make someone else’s day better when they are down and out, it makes it a little bit easier for me,” he said.

Nathan Dorn is survived by his siblings, Nikita Dorn and Dorinda Kopp, his daughters, Heather Craft and Katrina Dorn, and his grandchildren, Adyleana and Pangea (Katrina’s children) and Kahlan and Tanner. He was predeceased by his mother and father, and siblings Victoria Guest and Anthony Dorn. A celebration of his life is planned to take place in the coming month on Vashon.

— Jenna Dennison contributed reporting on this story.