Editor’s note: This article, reprinted from the Vashon Riptide, covers important imformation about issues related to students with disabilities at Vashon High School. What follows is parts one and two of the three-part story, which can be read in its entirety at tinyurl.com/yc6hafrk. Read more Riptide journalism at riptide.vashonsd.org.

By Lila Cohen, Savannah Butcher and Blake Grossman

For The Riptide

Overview: 504s and IEPs — what they are and how they came to be

This September, as students returned to school, controversy arose surrounding VHS’ ability to support students served by 504 plans and Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) along with students with disabilities.

The conversation has brought many suppressed issues to light, and has served as an opportunity for disabled students to share their experiences with not only VHS’s student body, but also with staff and administration.

VHS math teacher Lisa Miller feels the dialogue has been an important one and showed appreciation for the students who have raised their voices to question the ways that 504s and IEPs are being implemented.

“It’s a teacher’s job to figure out where we’re not serving students well, but if we specifically don’t ask the students, then we’re doing it blindly,” she said.

Staff members are looking at this conversation surrounding disability justice as an opportunity for positive change.

“When there’s a conflict, there’s always an opportunity to have conversation to seek a better, deeper understanding of the issue,” Vashon Island School District (VISD) superintendent Slade McSheehy said.

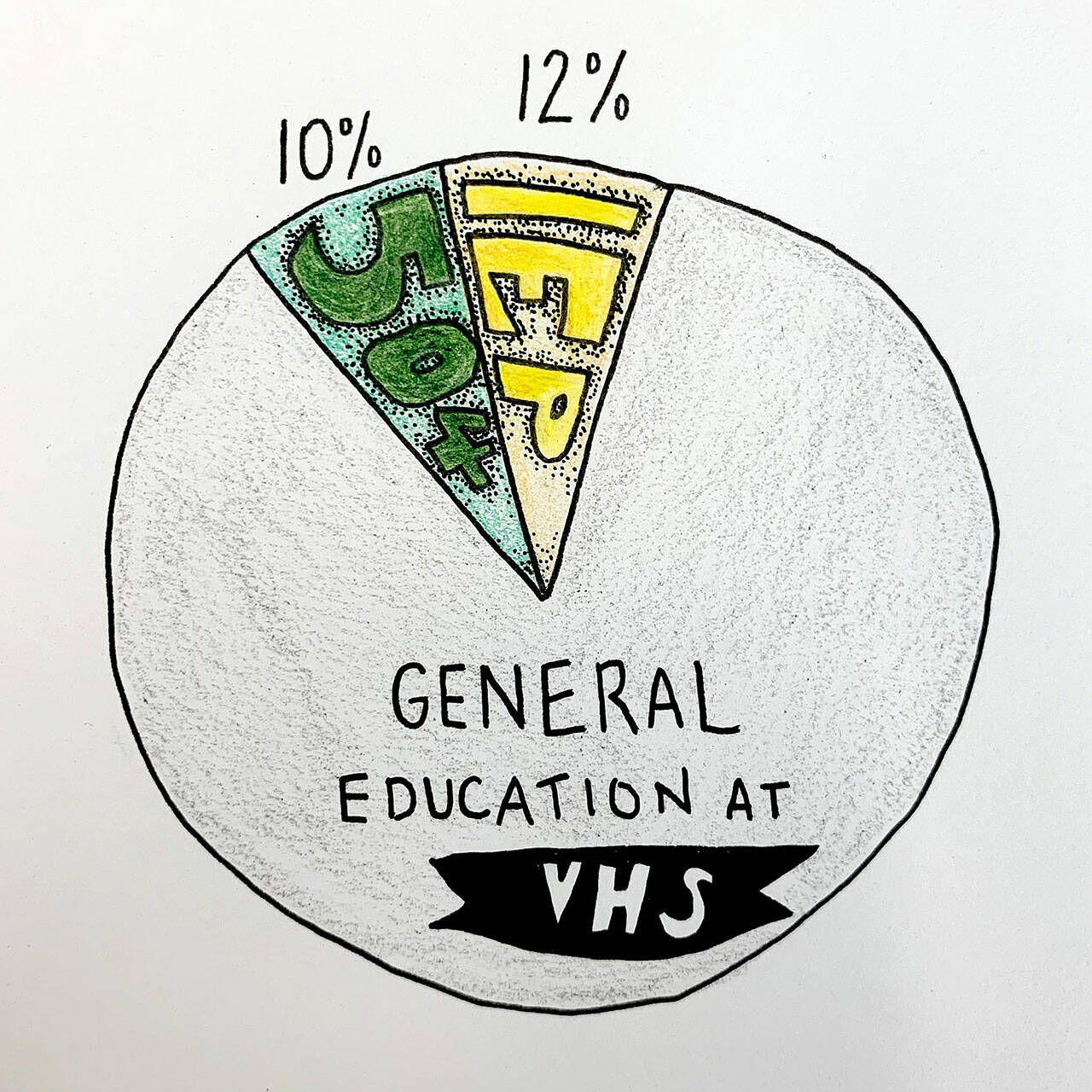

Today, 10 percent of VHS students are served by 504 plans, the product of Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, which was the first disability civil rights law passed in the United States. 504 plans grant students with disabilities the right to reasonable accommodations and seek to promote equal access to education. These accommodations are personalized to combat the barriers of a student’s disability, including things such as extended time on tests or assignments, preferential seating, the ability to take breaks from class, and access to modified content.

To be on a 504 plan, the student must have a documented disability and one that affects their ability to access educational opportunities. It is important to note that not all students with disabilities have 504 plans.

The Rehabilitation Act paved the way for the enactment of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or IDEA — previously known as Education for All Handicapped Children Act — which passed in 1975, and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which passed in 1990. The ratification of IDEA was the first time disabled students were granted the right to a public education under federal law.

Another 12 percent of VHS students are served by an IEP. Similar to how 504s are a product of Section 504, IEPs are a product of IDEA. And, as the name suggests, IEPs are specifically tailored to individual students.

VHS counselor Tara Vanselow explained the distinction between IEPs and 504s in a different way.

“With a 504, the finish line of a class is the same as everyone else’s finish line, and we’re providing support that helps a student get to that finish line. With an IEP, the finish line might be different.” she said.

IEPs and 504s are considered “tier three” support systems, which differ from “tier one” supports that all students received.

“SMART period is a tier one support — every student has access to SMART,” said VHS principal Danny Rock.

Rock further explained that “tier two” supports are designed for students already using “tier one” supports but still need more help. If the second tier of support doesn’t provide enough help, the next steps include IEPs and 504s.

Public schools receive no federal funding to support students with 504 plans but are legally required to evaluate and support the students who need them. School counselors are responsible for acting as the case managers for students served by 504s, and they, along with teachers, are the ones primarily supporting these students. IEPs however, are handled through a school’s special education department, which receives funding from the state and the federal government.

Even though funding is fairly proportional to the district size, support systems for students served by 504 plans and IEPs, as well as students with other disabilities, differ heavily between small and large school districts.

Kathryn Coleman, VISD Director of Student Services, has been a special educator for 35 years and recognizes the challenges that come with being a small district.

“Like every school district, we have a variety of students with a variety of needs. Figuring out how to meet all those needs is very challenging and difficult … In larger districts, the resources look different. There might be an entire group of people whose job it is to do nothing but work with kids who have much more significant disabilities. This isn’t true on Vashon,” Coleman said.

VHS special education teacher Beth Solan says that teachers try to accommodate all students as best they can.

“I would say, of any district I have ever worked in, the desire of teachers to meet students where they are has been, hands down, [at] the highest level [here at VHS] … Teachers in [this] district want to [make accommodations] and meet kids exactly where they are … in order for them to be successful,” Solan said.

Since VHS is a small school, there are sometimes more opportunities to support the needs of all students. Math teacher Miller said that she is proud of the fact that at VHS, students of varying abilities are all grouped together in classrooms, where they can benefit from teachers specializing in specific subject matter. Those teachers, in turn, are supported by special education teachers.

“One of the things I”m proud of in this school is that we’re no longer trying to do this ‘separate but equal’ [approach],” she said. “It’s never going to be equal. Having students of varying abilities in a general education classroom is awesome because those kids have a lot to offer other kids.”

VHS culture creates an echochamber

Being a small school of approximately 550 students not only affects VHS’ funding, but also creates a unique and sheltered culture. The small student body allows change to happen fast, but also for rumors to spread quickly. Despite Vashon preaching diversity, VHS can be a hard place to have needs that diverge from the majority of students.

“Vashon is a very hard place to be different. I’ve worked in a lot of different places, and while we are very tolerant, caring, and work hard to lift all people up on the island — there are lots of great examples of this — the truth is most are able to be successful without having to get extra help. If you need extra help, that can be a very lonely and frustrating experience on Vashon,” Rock said.

Wendy Axtelle, a senior at VHS and founder of the Disabled Student Advocacy club (DSA), sees this isolating atmosphere as an example of “freak culture.” Axtelle is visually impaired and has experienced this culture first hand throughout her time at VHS.

“You hear students judging you. You hear students talking about you behind your back; you see the looks like, ‘what’s wrong with them?’” Axtelle said. “You very much get this vibe of what people call freak culture, where people try to make you feel like a freak, which is not a good thing.”

Freak culture can develop into more severe bullying if left unchecked, said Axtelle, who said that while she had not experienced physical bullying, she knew other students who had.

When students ask for 504 or IEP accommodations at VHS, it can feel like they’re getting put in the spotlight.

“Lots of students can’t… pretend they don’t have a 504 or an IEP. Because you have to advocate for yourself so much, everybody knows. You’re getting called out, and people know that you’re not like them, and people like to attack people who aren’t like them,” Axtelle said.

Katherine Kirschner, a senior at VHS who identifies as disabled, is a strong supporter for more disabled student advocacy. She said that the VHS administration needs to do a better job of advocating on behalf of disabled and marginalized students.

“[Marginalized students] are the ones who have to fight for things they’re already being disadvantaged over,” Kirschner said.

Kirschner hopes to see more administrative support for students in order to level the playing field.

“I would love for administrators and staff to recognize that disabled students aren’t disabled on purpose. We’re not trying to get some slack, to get these accommodations so we don’t have to do anything. We’re asking for things that make our lives more livable, in a way that should be basic for all students,” Kirschner said. “I want us to start prioritizing those needs in a different way, and recognizing that it shouldn’t be the marginalized group’s job to advocate for themselves all the time. We’re really good at it because we get all the practice, but we shouldn’t have to. I like to see my friends have a day off, where people [automatically get] what they need.”

Staff agrees that students shouldn’t have to advocate for their basic needs to be met.

“I think it’s really wonderful … when students are advocating. I don’t think it’s great when they have to advocate for themselves,” said Solan.

When using the social model of disability, the reliance on self-advocacy is seen as a shortfall of the community. The model was created by a collection of disability rights activists in the 1970s through ’80s, and the phrase was coined by Mike Oliver in 1983. Instead of disability being a personal problem, the theory instead says it is a shortcoming of society for not being able to accommodate all people.

“VHS very much prescribes to the social model of disability. If you’re not one of the few students at this school that [this school] works really well for, then you’re going to be considered an outsider,” Axtelle said. “Whether you identify as disabled or neurodivergent, or if you have a 504 or IEP, if you’re considered an outsider to the school, you’re often going to be considered less than the people [who thrive at VHS].”

Axtelle thinks VHS could be a part of a larger movement supporting disabled student advocacy.

“This isn’t just a small group of students that are having this problem. It’s a universal thing, and we have to have a universal structural change,” Axtelle said.

Part three of this article will be published in the Dec. 30 issue of The Beachcomber. Lila Cohen and Savannah Butcher are deputy editors of the Riptide. Blake Grossman is a reporter for the Riptide.