The high cost of gas led to a creative solution to save money.

Gene Amondson, an Islander perhaps best known for his presidential candidacy with the Prohibition Party slate, has a new platform.

He’s campaigning for others to follow his lead and “get on the water wagon,” by adding to their cars a simple device — a combination of water, baking soda and electricity — that can clean engines, increase gas mileage and reduce pollution, he says.

Amondson’s Honda Civic hatchback now runs on hydrogen as well as gasoline; he says he expects the vehicle will soon get up to twice as many miles to the gallon with an added kick of hydrogen.

“It makes your gas burn really well,” Amondson said. “It’s good for your car because it’s running clean.”

Though he’s using technology that’s more than 200 years old to inject hydrogen into his vehicle’s carburetor, Amondson has garnered local television attention for being one of the first to use this model of hydrogen production on a vehicle. He appeared on King 5 TV News this month, showcasing his updated vehicle.

He and Doug Schwarz, a “car junkie” friend of his, installed a “hydrogen conversion kit” on Amondson’s car on Sept. 2. The kit is composed of six glass canning jars, each with a stainless steel wire spiraling through the inside.

After filling each jar with water and a few teaspoons of

baking soda (to increase the

water’s conductivity), and connecting the steel wires to his car’s battery, Amondson’s vehicle was hydrogen- and gasoline-powered.

Electricity from the car’s battery runs through the water, and electrolysis sends hydrogen through small tubes into his Honda’s carburetor, he said, mixing with the gasoline and air that’s already there. Electrolysis, discovered in 1800 by two Englishmen, is the process of running electrical current through water to separate it into oxygen and hydrogen, the two gaseous elements that compose it.

“On 1,300 miles, I’ll only burn a cup and a half of water,” Amondson said. “But that cup and a half went to make hydrogen. … The hy-drogen is like air in there, and makes the fire hotter — like burning high-octane gasoline.”

He said the conversion kit took two hours to install, and costs $500 including installation. Amondson is the fourth person to buy the low-tech kit from Schwarz, who also converted his vehicle and experienced dramatic improvements in mileage.

Islander John Sherman, a heavy equipment operator at KimmCo, installed the kit himself on his diesel Dodge truck.

“It just gives you more power and better mileage,” Sherman said.

Lou Engels, owner of Engels Repair & Towing, said he’s looking forward to learning more about hydrogen-powered vehicles.

“It’s got to be a good thing,” he said. “Technology is coming on now like it never has in the past, and there’s going to be a lot for people to learn.”

But some chemists and environmental experts question the kit’s efficacy and mechanism for action.

“You’re using energy to make the hydrogen, and that’s not an efficient conversion,” said Rita Schenk, executive director of The Institute for Environmental Research and Education, a nonprofit on Beall Road.

“It may make a more efficient engine,” she added, “but it’s not obvious to me how this would work.”

Tom DeVries, a science teacher at Vashon High School, said the reason the technology, which seems so simple at first glance, is not widely used may be that it’s too expensive, not safe enough or inadequately tested. But he couldn’t say conclusively why the low-tech kit hasn’t caught on.

“I don’t know if I’d be encouraging people to do it,” he said.

Still, “the concept is plausible and the mileage increases are possible,” DeVries added.

Hydrogen is the universe’s most common element, but it never occurs by itself in the natural world. It is always combined with another element. President Bush has expressed interest in hydrogen as an alternative fuel, pledging $1.2 billion for research on hydrogen

power in 2003 to reduce the nation’s dependence on oil.

But the United States faces a roadblock — the high price of electricity. Iceland, on the other hand, is a nation that has a great deal of volcanic and geologic activity, which drives the price of electricity down for the island country. There, hydrogen is much cheaper to produce.

Iceland already depends on geothermal or hydroelectric power for 70 percent of its heating and electrical needs and began exploring hydrogen-powered buses in its capital of Reykjavík last year, according to CNN. Only the transportation sector is hooked on gasoline, and that may soon change.

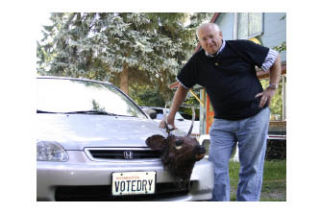

Amondson, for his part, sees great possibility for the future of hydrogen power, starting on a small scale — under the hood of his Honda, which has 117,000 miles on the odometer and a faux deer head on the grill.

He’s only traveled 30 miles since introducing hydrogen to the car’s engine, but says it feels better to drive, and he doesn’t have to push the gas pedal down very far to get a punch of acceleration.

“Mine ran good when I got there, and it runs good now,” he said. “This could be so simple. I want us all to have efficient cars because we’re all poor. I want cleaner air. I did it first because I want to get it out there.”