Vashon High School teacher Martha Woodard remembers the early days of teaching, when she had current textbooks and a classroom budget that allowed her to subscribe to a New York Times supplement on current affairs.

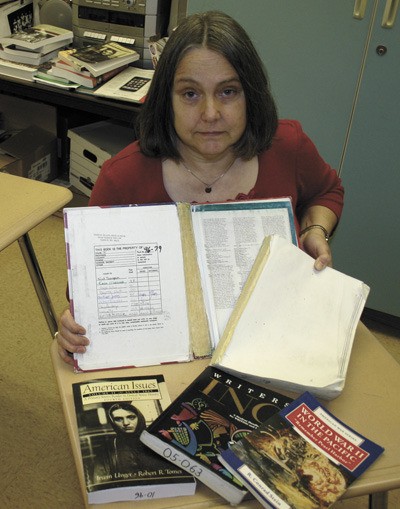

But budget cuts forced her to drop that subscription long ago. And these days, Woodard, who teaches American studies and college-prep English, spends a portion of her summers rebinding aging books that are falling apart.

Little wonder, then, that Woodard, who began teaching in 1982, was thrilled to learn that a King County judge issued a ruling ruled last week underscoring what she and many teachers know intuitively — that the state has failed for years to meet its constitutional mandate to fully fund public education.

“I was ecstatic,” Woodard said. “I have no idea what the upshot really will be. But what it does is bring honesty to our legislative process. (Lawmakers) always say they’re pro-education, but they’ll cut funds in one area or mandate things without funding.”

After a six-week trial last fall, Judge John Erlick issued his 75-page ruling from the bench on Thursday — a strongly worded decision that the state had failed to comply with the Washington Constitution, which calls education the “paramount duty” of the state.

The case, McCleary vs. the State of Washington, was brought by a coalition of school districts, parents, teachers and community leaders, working together under the auspices of the Network for Excellence in Washington Schools, an organization formed to tackle the long-standing issue of public school financing in Washington.

The lead plaintiffs were two mothers — one from the Chimacum School District and another from Snohomish — both of whom took to the witness stand to describe ill-equipped schools that they believed were failing their children.

The state, which argued that it was indeed adequately funding education, has yet to decide if it will appeal the decision, considered the biggest lawsuit over public school financing in more than 30 years. “There’s a lot in there. It’ll take some time to digest it and analyze what the legal implications are,” said Dave Stolier, a senior assistant attorney general who was part of the legal team.

And even if the state doesn’t appeal, it could be years before the implications of the decision reach local school districts.

Erlick, who said he would not “micromanage education,” left it up to the Legislature to decide how much more money schools should receive and when. Last year, the Legislature passed a bill that set 2018 as a deadline for making a number of changes in how the state funds education.

It’s possible, observers said, that Erlick’s decision will strengthen lawmakers’ resolve to fulfill that 2018 deadline — some feared lawmakers might renege on their legislative promise — but not rush the process.

Even so, Vashon Island School District officials said, the decision was hugely encouraging. Vashon, like school districts around the state, has been feeling the effects of declining state funding and rising costs and is braced for another tough round of budget cuts and possible lay-offs this year.

“If it really gets fulfilled, it’s huge,” Laura Wishik, who chairs the Vashon school board, said of Erlick’s decision.

The plaintiffs, she noted, described decrepit buildings and aging textbooks that are falling apart. “Well, we’ve got that, too. It sounded very familiar.”

“I think it’s a big deal,” added Superintendent

Michael Soltman. “It’s a clear recognition that the Legislature has failed to amply fund education.”

Because of the state’s de-clining financial support, the Vashon school district has increasingly looked to local levies — meant to provide enhancements to a district — to cover basic needs. It’s also shifted more costs to parents: Seven years ago, for instance, parents paid $65 to enroll a student in a sport; this year, it costs $100.

And while the amount the state pays per student has not fallen much over the last few years, other supplemental funding has been drastically reduced, said Tom Dargel, the district’s business manager. The state, for instance, provided nearly $400,000 to the Vashon school district in 2004 for what it called “student achievement” — funding the district used to reduce class size. This year, that line item fell to $30,000, he said.

Because of the steady decline in state funding, Vashon has had to tighten its belt over the years, Soltman said. Today, it provides almost nothing in the way of professional development. And when textbooks are replaced, it’s usually with funds raised by the PTSA, he said.

Last year, the district reduced its librarian staff, Soltman added, so that there’s no longer a librarian at Chautauqua Elementary School and only a half-time librarian at McMurray Middle School. The district has a librarian aide at Chautauqua, providing some services. Still, Soltman noted, the loss of librarian services is noteworthy.

“When you don’t have a librarian, you don’t have someone taking care of the collection; students have less access. … It just restricts what can go on in the classroom,” he said.

But the decision comes at a tough time for the state, which is facing a $2.6 billion deficit. As a result, some said, it could have another effect, adding momentum to the growing call for tax reform.

State Rep. Sharon Nelson (D-Maury Island), an advocate for a state income tax, said the state is struggling financially in part because of its heavy reliance on the sales tax, a source of revenue that diminishes during a recession. The ruling “certainly opens a dialogue” for a state income tax, Nelson said.

Woodard, the VHS teacher, said a change in education funding can’t come soon enough. Just last week, a student turned in a copy of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” and “it fell apart in our hands,” she said.

A former book binder, she said she repairs 10 to 15 books each summer. Groups like Partners in Education and the PTSA, she added, are making the difference in her classroom.

“If it weren’t for their generosity,” she said, “the schools would simply be on their knees.”

Read Judge John Erlick’s decision.