By Bruce Haulman and Terry Donnelly

For The Beachcomber

Dockton’s name reveals the story of its past as a bustling center of maritime activity.

In the 1890s, Quartermaster Harbor was an industrial center with brickyards, lumber mills, several shipyards, and a dry dock.

When Port Townsend businessmen were unable to fund the completion of the large dry dock they had designed and started to build, a group of businessmen from Tacoma, including M.F. Hatch of Vashon Island, formed The Puget Sound Drydock Company, purchased the dry dock, and in November 1891 towed the still-unfinished dry dock from Port Hadlock to Dockton where it was completed.

Measuring 102 feet wide by 325 feet long, it was the largest dry dock west of the Mississippi. The weight of the nails alone was 8,400 pounds. The dock, first used in March 1892, had more than 80 employees who worked the yard by June. It served as a repair facility for the busy maritime industry throughout Puget Sound.

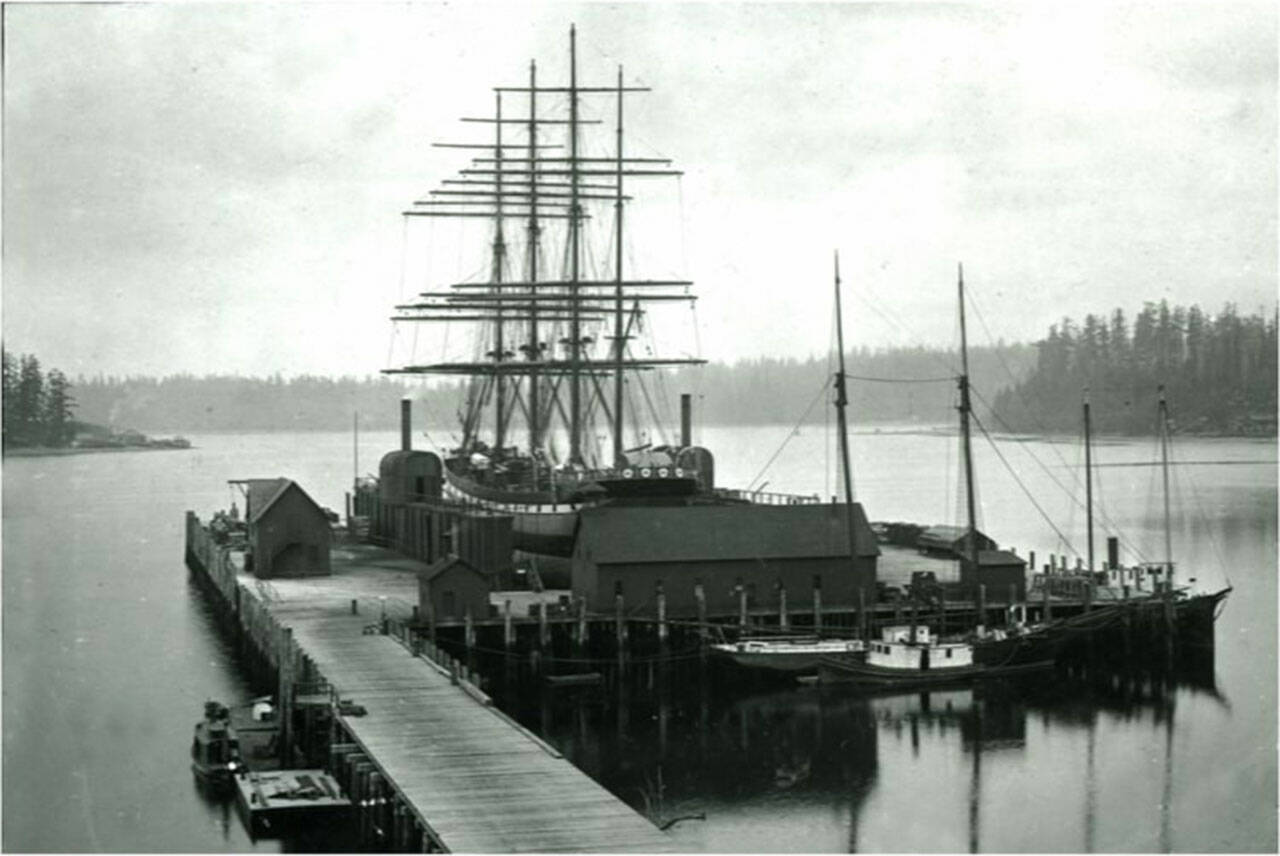

The first vessel repaired was the steamer Flyer, followed by repairs on Wetmore and City of Everett, which were steamers originally built on Lake Superior. In October, the British warship Hyacinth was repaired. The Oliver Van Olinda photo of the dry dock was taken in 1893 and shows the steel four-masted 326-foot barque, Olivebank, in the dry dock undergoing repairs.

As the dry dock business grew, so did the town. Dockton derived its name from the presence of the dry dock, which prospered with the advent of the Alaska gold rush and the Spanish American War. This increased activity brought an influx of skilled immigrant shipwrights from Norway and Croatia. Many of these immigrants also began fishing and farming as well.

A large three-story hotel housed workers and a series of homes were built for the dry dock managers. The houses were called Piano Row, because they were the only houses with parlors large enough to hold a piano. In addition, the growing community added a store, worker’s homes, docks and net sheds for the fishing fleet, and small farms to supply food. Regular steamer service to Tacoma also made Dockton a thriving community.

Industrially, Vashon was moving into what Carlos Schwantes has termed the “Post-Frontier World.”

The boom-and-bust cycles of the 1890s were followed by a brief expansion of the Dockton shipyards at the turn of the century, followed by a collapse with the sale and move of the dry dock to Seattle.

A bitter strike, precipitated by the hiring of island men to work overtime, roiled the Dockton shipyards in 1895, as workers sought higher wages and more secure working conditions. The dispute was quickly settled in favor of the workers. Within a year, the depression dragged down demand, but after the recovery at the turn of the century, the shipyards returned to actively repairing and building ships.

In 1905, the dry dock was sold to John T. Heffernan, who owned the Heffernan Engine Works in Seattle. Heffernan continued to operate the dry dock until 1907, when workers who had not been lured away to the Klondike Gold Rush demanded better pay. Rather than submit and pay higher wages, dry dock manager E.C. Warner shut down the dry dock and, within two weeks, Heffernan began to make plans to move it to Seattle. The dry dock stayed put another year, but in 1909, it was moved to Seattle.

The era of the island as a major shipyard began a long slow decline, although boat construction continued for another two decades at the Martinolich and Stuckey yards.

With the dry dock gone, and as the shipyards began to close in the 1920s, Dockton relied on the fishing fleet and berry farms. The fishing fleet was divided between the big seine trawlers operated by the Plancich, Ljubich, and other families; and the smaller one or two-man trollers operated by the Nelson, Jensen, and other families.

The berry farms — filled with currants, gooseberries, loganberries, and strawberries — prospered and the Martinolich Hotel was converted to a packing plant until it was remodeled into the Dockton School. The Cod Fish Dock canning plant operated intermittently during this time, processing whatever was available from cod, to salmon, to clams.

Prohibition brought a new “industry” to Dockton as the fishing fleet would occasionally hide a few cases of illegal alcohol in their full fish holds to transport across the border as they returned from Alaska. Several “pleasure boats” were built in Dockton during Prohibition.

The Great Depression of the 1930s also brought the WPA to Dockton and Dockton Park and sidewalks were built with Federal funds administered by Theo Berry, the owner of the Dockton Store.

After World War II, both fishing and farming began another long slow decline that lasted into the 1970s.

Dockton became more of a residential village, and when the Dockton Store closed in 1979, residents became even more dependent on Vashon Town. The gentrification that has characterized the island since the 1990s, has also had a major impact on Dockton as homes have been purchased and remodeled, or new homes built on land that was once farms or shipyards.

Once an industrial center, Dockton is now a quaint rural pause for boaters and tourists who want to escape the city, and for a new generation of retirees, second homeowners, telecommuters, “real” commuters, and a remnant of those families who settled there to build the boats, catch the fish, and grow the berries that forged the community.

The Dockton Historic Trail allows visitors to walk the streets of Dockton, see where the historic buildings were located, and learn more about the fascinating history of Dockton, its dry dock, and the changes that have taken place.

— Bruce Haulman is an island historian. Terry Donnelly is an island photographer.