I read Ed Swan’s, “The Birds of Vashon Island,” before I lived here, and it’s one of my all-time favorite bird books. On page one, he describes the aim of his book as “illuminating the connectedness of the birds to the condition of the land and water on which we all depend.”

Connectedness is a watchword of the holistic naturalist signaling the complexity of our natural systems. Swan is a big-picture birder who explains how birds are connected to the environment of our dynamic island, how they’ve been affected by radical human-made environmental changes in the past and how future changes on the island and the planet might affect them.

In his book, Swan describes Vashon’s transformation from old growth coniferous forest, to forests lightly managed by S’Homamish natives, to “a vast wasteland of slash” so thoroughly clearcut by settlers that “by the beginning of World War I, one could walk from one side of the island to the other without seeing a mature tree.” While some birds, such as spotted owls and marbled murrelets, disappeared with the old growth forests, others began colonizing the new open spaces and developing farmland. Red-tailed hawks, barn owls and western bluebirds were among the 20 species that arrived and thrived in the wake of the clearcut. Failed farms and another world war caused Vashon’s open space to revert to forest so that more than 70 percent of the island was wooded again by the millennium. This time, the forests were mostly mixed hardwoods, and another season in the avian fashion show began: Bluebirds and meadowlarks were out; goldfinches and chickadees were in.

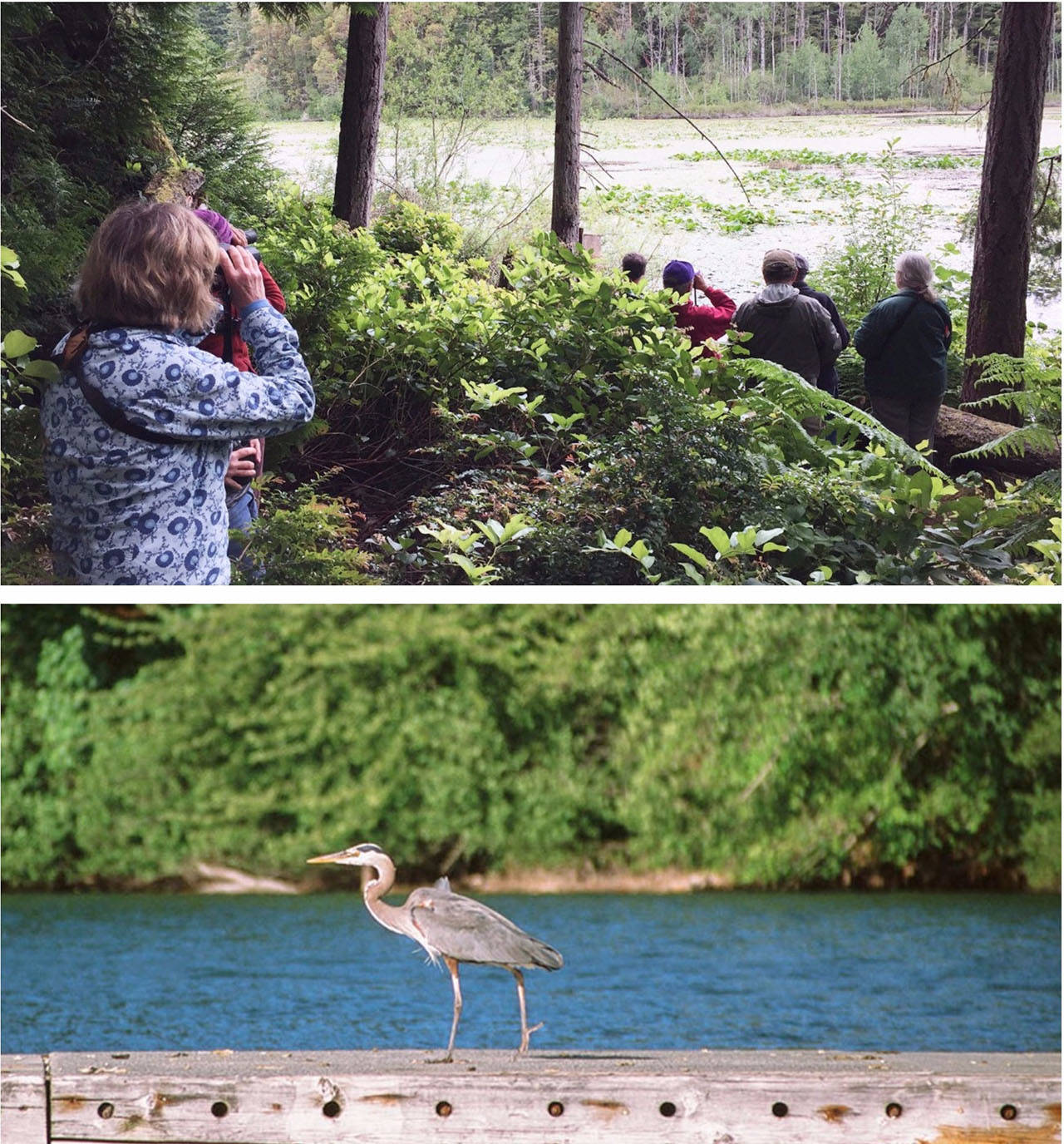

I was lucky to snag the last spot on Swan’s most recent Seattle Audubon field trip to Vashon, during which we saw species connected to each era of the island’s natural history. This kind of birding is more than a nerdy day of wing bars and eye rings. It goes beyond telling the difference between a yellow warbler, a yellow-rumped warbler and a common yellowthroat (all three were spotted on this trip). It’s a chance to see birds in the context of their relationship to the environment and the changes that have occurred to both over time.

Three birds we saw at Fisher Pond — wood duck, great blue heron and tree swallow — illustrate some of the unique histories of species’ rise and fall on Vashon. Wood ducks probably didn’t exist on the island until farmers built ponds. Now, they’re common breeders, which is fortunate since Swan recalled watching ducklings getting picked off by a bald eagle while he was leading an elementary school field trip here.

Great blue herons used to nest communally in large rookeries around Vashon. Bald eagles, common in the late 19th century were almost extinct by the 1960s. Once eagle populations recovered, thanks to the ban on DDT and federal protections, they preyed on heron chicks, and the rookeries were abandoned. The herons still visit Vashon, but they can no longer nest here.

Of the four species of swallows on Vashon, tree swallows seem to be having the hardest time adapting. They hunt insects that decline during cold, wet springs and are out-competed for nest cavities by European starlings and English sparrows. So a pair occupying a nest box on Fisher Pond was a welcome sight that prompted master birder Sue Trevathan and Vashon Nature Center’s Kathryn True to discuss building more nest boxes around the pond. And just like that, nerdy birding becomes action that may help threatened species adapt to change.

Bird watching with Ed Swan goes beyond identifying birds to become a practice of identifying with birds, as we watch them trying to make a living or find a home on an island dealing with a past, present and future of constant change. As our views of nature have the potential to tell us about ourselves, we might look closely at the ways in which we identify with the birds of Vashon.

— Chris Woods