In his kitchen overlooking Quartermaster Harbor, Jim Stewart, the founder of Seattle’s Best Coffee, grinds coffee beans from his farm in Costa Rica. The kettle whistles. Stewart pours the steaming water over the grounds, using the drip-brew method to fill a narrow, well-worn thermos. There’s not an espresso machine or coffeemaker in sight. Stewart takes his coffee black, in a demitasse.

While today Stewart is known on Vashon and beyond as the man who brought fine coffee to Seattle, 44 years ago he never drank the dark beverage. Ice cream, not coffee, was the name of Stewart’s first retail game.

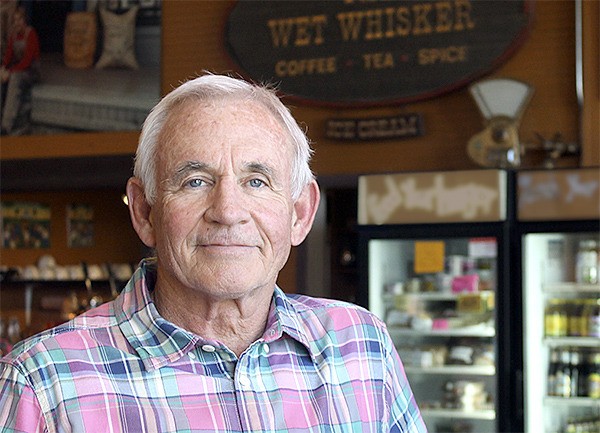

Stewart sold 18 flavors of ice cream at The Wet Whisker, a shop he opened in Coupeville in the summer of 1969, between graduating from the University of Washington and starting optometry school in California. As Stewart tells it, the path to Seattle’s Best Coffee began with the two women who did The Wet Whisker’s taxes.

“At the end of that first summer, they said we have this donut recipe — to hear them talk it was going to save the world — and there are these great coffees in Monterey, California,” Stewart recalled, shaking his head with a humorous glint in his bight blue eyes. The women said that if Stewart added coffee at The Wet Whisker, they’d give up their recipe.

Not intending to leave optometry, let alone sell coffee, Stewart found the women’s suggestion rattling around in his mind as he drove toward Los Angeles and optometry school. So he stopped in Monterey to check out JJ Adams coffee. He liked the ambiance of the shop, the burlap bags on the walls and how it smelled. But the eureka moment came when Stewart discovered The Coffee Bean, a specialty coffee shop in Los Angeles.

“They had coffee samples, and it was like whoa, this coffee has flavor. Each one is different from the other. So I started drinking coffee,” Stewart said.

And he started selling it at The Wet Whisker, buying from a wholesaler in Portland. Roasting came along the following summer, after Stewart learned the art while working at The Coffee Bean. By the third summer, Stewart’s younger brother Dave became a partner of The Wet Whisker, and in 1971 the two opened another store at newly developed Pier 70 on Seattle’s waterfront.

When Stewart left optometry to sell coffee, he said the move happened because he was going through a divorce and not thinking clearly. But coffee and the success of The Coffee Bean also drove the decision.

“That coffee was different. People didn’t know what it was,” Stewart said, refilling his tiny cup with the piping hot liquid from his thermos.

In those days, coffee was about $1.59 per pound retail, Steward said. In grocery stores one could get three pounds on sale for 33 to 39 cents. “But it just tasted awful,” he said.

Visitors to Stewart’s house are greeted by an impressive elk head hanging in his entryway. It is one of many trophies for the man who grew up hunting in northern Wisconsin. Stewart is still an avid hunter, but he credits the time he spent working at The Coffee Bean for opening his eyes to a whole other world than the one he grew up in.

“People were coming in like Robert Redford and Cary Grant. I mean for a 21- or 22-year-old kid from Wisconsin, you could hardly believe you were there,” he said. “But I learned the biz and then came back up here.”

He brought his entrepreneurial spirit and Midas touch with him. After Pier 70, Stewart landed a contract for an ice cream concession at Seattle Center. It became the largest hand-dipped hard ice cream concession on the West Coast, and sales funded his coffee business.

They also began roasting in 1984 on Vashon, in the basement of old Granny Dugan’s house, the current site of The Minglement. Stewart had moved to the island in 1981, built a log house and liked the idea of not commuting to a warehouse in Seattle.

Next, the brothers opened a retail store in Bellevue Square. But the company name, The Wet Whisker, and the burlap bag look were not for the Bellevue clientele.

“We decided, based on someone’s decision, to call ourselves Stewart Brothers Coffee and laid out this whole new thing,” Stewart said.

With high traffic flowing through well-designed stores and a focus on product quality and customer service, the business soon reached $1 million in sales when the brothers met a subsequent challenge. They needed money to grow. It was the Carter era, and the financial risk came in interest rates close to 18 percent. Riskier still was Stewart’s decision to buy coffee direct from growers — after a trip to Indonesia, Central and South America — a practice that was unheard of at the time.

“Nobody was doing that, not even the big companies,” he said. “I figured we could buy less expensively and get better quality, but you needed to buy larger quantities, which required funding.”

His old employer, the owner of The Coffee Bean, agreed to go in with him on the coffee and shipping costs. But just as the business began to expand, Stewart Brothers Coffee in Chicago discovered Stewart Brothers Coffee in Seattle, and they didn’t like it. Plus they had a trademark for the name. The brothers switched the name to SBC, and in 1987 the company became an overnight sensation.

SBC won a tasting contest held by the Seattle restaurant McCormick and Schmidt, and that night on every radio and TV station in Seattle, SBC morphed into Seattle’s Best Coffee.

From there the company’s trajectory soared high and fast, with shops all over Seattle and sales reaching $5 million. SBC had to restructure again, and this time Stewart bowed out, selling 60 percent of his share. However, Stewart continued to keep his hand in the business, doing what he loved most, buying the green coffee beans. And he did so until the day Starbucks bought the company in 2003.

“Which I can tell you,” Stewart said, “was not part of the plan.”

Though there was a worry that Stewart’s beloved shop at Center could change into a Starbucks, the company did not buy the building and only wanted what was new at SBC, like computers and cash registers. They had no use for the old roasters on Vashon or any of SBC’s history, which meant Stewart was left with a museum when islander Eva DeLoach approached him to rent the building.

“She knew nothing about coffee, but was afraid of nothing,” Stewart said.

Stewart’s former roaster Peter Larsen showed DeLoach how to roast, and she wanted the museum, so he didn’t have to move his collection of antiques.

“It was perfect,” he said.

Today, Stewart spends half the year on Vashon and half the year in Costa Rica, on his farm, Tierra del Gato, with his wife, who comes from a third-generation coffee growing family. Tierra del Gato became Costa Rica’s first certified organic coffee farm, where Stewart still grows the old varieties of coffee, the non-hybridized beans, the very beans whose rich aroma rose out of his thermos.

Sales from his coffee beans now help fund the Vashon Island Coffee Foundation. Stewart’s nonprofit originally was established to assist Santiago, Vashon’s sister city in Guatemala, but over the years has also helped with flood relief and earthquake assistance in El Salvador and Costa Rica.

Inside The Mingelment, which he still visits, Stewart talks to happy patrons, while evidence of his storied career, beginning with The Wet Whisker, hang overhead, and a shelf of coffee bean bags visually tells the company history. With his easy laugh, Stewart reminisced that the two accountants never did ante up on their part of the deal.

“We didn’t get the donut recipe, thank heavens,” Stewart said. “But we did get the coffee.”