To step into Shane Jewell and Emily Pruiksma’s home in Paradise Valley is to enter a world made by hand — their own hands.

Consider first where they live: Tucked behind Plum Forest Farm, past wooden gates, a chicken coop and several Scottish Highland cows, sits a pair of yurts, the couple’s home and music studio. Inside, the hand-made feel begins with the warm patina of the hand-packed earthen cob floor on up to the hand-bent poles supporting the hand-sewn cover.

Then look around: There’s the folding rocking chair Pruiksma made. Jewell’s handcrafted 17-foot umiak. The beloved hurdy-gurdy he built. A sturdy worm bin Pruiksma crafted.

They don’t own a car. A wood-fired cookstove heats the hot water tank. They power their washing machine by pedaling a stationary bicycle. Energy for their electric chainsaw and rototiller comes from the sun. Their 1920s-era treadle sewing machine — gifted to them by an Islander — is a steady workhorse.

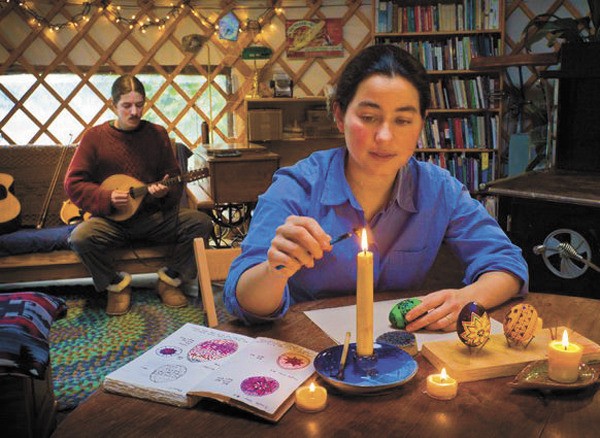

And these days, as they ready themselves for Vashon’s 29th annual Art Studio Tour this weekend, their handcrafted lives are on display more than ever. Hand-dipped beeswax candles — made in part from beeswax they collected on Vashon — line a table. Etched-glass candle holders and pendant necklaces line another. And Pruiksma’s speciality — delicately decorated Ukrainian eggs that have begun to draw repeat visitors to their small yurt — are being readied for the tour.

Saturday and Sunday, when visitors follow the narrow path to Jewell and Pruiksma’s yurt, they’ll likely find Pruiksma bent over a blown egg, a candle to warm her kitska — or hot wax pen — glowing softly next to her, as she plies her craft.

The two enjoy the studio tour, as it’s a chance, they note, to connect with friends and neighbors. But more often than not, it’s also an opportunity for them to talk about the lifestyle they’ve chosen and the philosophy that imbues it.

“We get people who come and see the large picture of it, and it kind of fires them up. And others look a little confused by it,” Pruiksma noted. “We end up talking a lot about our space as well as our art, because so much of what we do is part of a larger picture, … part of our effort to live in a way that’s a lot lower impact.”

If anyone on Vashon could be said to piece a life together, Shane Jewell and Emily Pruiksma, both 33, could. He teaches at the Homestead School; she works two days a week at Vashon Library. He offers music lessons to a dozen or two students in 10 different instruments. She builds and sells worm bins. Together, they grow much of their own food.

Fourteen years ago, Jewell and Pruiksma never imagined they’d be living life off the grid in a hand-crafted yurt on a small organic farm. But that was before they staffed the 600-member food co-op kitchen of Oberlin College in Ohio.

The couple attended Oberlin between 1997 and 2001, where they met in the co-op kitchen. Both natives of Puget Sound, Jewell and Pruiksma bonded over nostalgia for the misty rain of the Northwest and their mutual passion for music. Pruiksma, an environmental studies major, coordinated the co-op’s local food program, buying produce from the region’s Amish farmers. Jewell, a math and music major, was the pizza chef.

Before long, Jewell joined Pruiksma on her buying trips to the country, where they visited farms and marveled at the self-sufficient lifestyle of the Amish farmers.

“They were really inspiring,” said Pruiksma. “They lived close to the land in a tight cohesive community. … There was something very attractive about their hands-on life.”

Though Pruiksma and Jewell grew up as urban dwellers, in Seattle and Bellingham respectively, they began to ponder how they, too, could be in community while living rooted to the land.

“We were studying things in school that were so theoretical — we really wanted to learn these skills connected to place,” Jewell said. “At the same time we were studying all the problems in the world, the big name issues of climate change, breakdown of communities, destruction of farmland. … We decided we’d rather be part of the solution.”

Like so many times to come for this adventurous couple, one experience led to the next. Junior year, Jewell and Pruiksma traveled the world visiting five countries as part of a global ecology program. At a collective called Timbaktu, a volunteer organization working for sustainable development in a drought-prone area of India, Jewell and Pruiksma were again inspired by what they saw. The collective had re-instituted traditional methods to retain water, transforming what had become a desert into the forest it once was.

But it wasn’t just the ecological restoration that the young couple found inspirational; it was also the way the people in the collective went about their work, using music and dance to build a community. When Jewell and Pruiksma arrived, they recalled, some of the local musicians put on a traditional dance for them.

“Music seemed like such an essential part of what they were doing,” Jewell said. “And they weren’t only trying to rebuild a place, they were trying to rebuild a community that could take care of the place.”

Returning to the Northwest after college, the duo dreamed of living life like the communities they visited, but they didn’t know where or how. That’s when serendipity intervened. A call from Amy Bogaard of Hogsback Farm brought the couple to Vashon. Bogaard is a friend of Jewell’s aunt and uncle, Joanne Jewell and Rob Pederson, owners Plum Forest Farm; she contacted them in search of interns, learned of Jewell and Pruiksma and thought they’d be ideal.

Jewell and Pruiksma accepted, and the job turned out to be an opportunity for them to learn an essential foundation for their vision: how to grow food.

When the internship ended, the couple took what looked like a detour on their path to sustainable living, choosing to walk the Pacific Crest Trail from southern Oregon to Canada. Influenced by the self-sufficient farmers back in Ohio, they sewed much of their own gear, fashioning mosquito-proof clothing, a lightweight tent and backpack.

In the middle of the preparation, Pruiksma remembered watching Jewell walk across the meadow at Plum Forest Farm, where they were living, with a bundle of sticks. An enthusiastic Jewell told Pruiksma that he’d learned how to construct a yurt and thought they should build one.

With a gentle nod towards her partner, Pruiksma noted that Jewell knows how to dream and see what’s possible while she has the slow staying power, and that makes for a very good partnership. So before leaving for the Pacific Crest Trail, together they built a small yurt — once again, with no notion of where the project would lead.

Determined to do the Pacific Crest Trail mostly by their own human power, Jewell and Pruiksma set off from Vashon on their old middle school bicycles, riding down the coast for a month and ending up in Ashland, where they shipped the bikes home and began the 1,000-mile hike.

“It was this whole process of slowing down,” Pruiksma said. “Walking is a perfect time for dreaming. We didn’t know it then, but it was really a pivotal time.”

Upon their return, in 2005, they began construction of a larger yurt. The smaller one now serves as Jewell’s music and tutoring studio.

And in 2008, again in an effort to re-create the beauty and wisdom of that collective in India, Jewell and Pruiksma decided to form the Free Range Folk Choir, an a cappella group that performs world music in four- and five-part harmony. The economic downturn was beginning to hit Vashon, the couple recalled, and they saw the choir as a way to lift spirits and foster community, just as music had in India.

The choir now numbers 80 singers. Earlier this month, its pre-Thanksgiving concert drew a standing-room-only crowd to the Methodist Church.

The couple admits they sometimes feel isolated on the Island because of the course they’ve charted. Many talk of sustainable living; few, they note, are living it to the degree they are. But then they remind themselves that the majority of the planet lives as simply as they do. And, to keep his priorities straight, every morning Jewell recites Wendell Barry’s “Mad Farmer Liberation Front Manifesto,” which calls for redemption by living close to the earth and cautions against the lure of materialism, as then “not even your future will be a mystery any more.”

“And that is the great tragedy we are trying to avoid,” said Jewell. “Dreams are a mystery, you have to take them one at a time. … We didn’t have any plan to end up doing what we do or being the way we are, and yet looking back, there is no more direct path we could have taken to end up where we are. Each part of our journey was absolutely essential … to figure out what our dreams are.”

Earlier this fall, Jewell and Pruiksma set out in their hand-made umiak to explore the waters surrounding their Island home in south Puget Sound. If, as the couple believes, a slow journey allows time to reflect, then one can’t help but wonder what dream they’ll be living next.

— Leslie Brown contributed to this article.