From Bruce Haulman’s geranium-filled deck overlooking Tramp Harbor, low tides reveal vestiges of Vashon’s first ferry boat landing, circa 1916. Were it not for an island-wide vote in 1921 to move the dock to the north end, Haulman notes, he might be watching the comings and goings of the Issaquah or the Tillikum from his cedar-shake house perched above KVI Beach.

Had Islanders not voted in 1939 for the ferry to unload at Fauntleroy instead of downtown, Vashon today might look a whole lot more like Bainbridge Island, he said. Or consider the implications of King County’s budget crisis of 1960: Were it not for that, the county’s plans for a bridge might have come to fruition and Vashon today would be connected to the mainland.

If anyone could be dubbed Vashon’s unofficial historian, Haulman could. And to spend an afternoon with him is to see the Island differently — to see what Haulman calls the “contingencies of history” that shape a place, that determine a whole course of events for decades, even centuries, to come.

“The bridge wasn’t built, so Vashon has remained a rural enclave in the middle of what I call the Puget Sea,” Haulman said. “It didn’t have to happen the way it did. A few changes, the bridge would have been built, and Vashon would be very different. It was the luck of the draw, if you will, luck of historical contingency.”

Haulman, 68, has given over much of his life to understanding these historical contingencies. Last month, he retired as a history professor at Green River Community College. He’s taught Island history at Vashon College, created a Vashon history website and writes the “Time and Again” column for The Beachcomber.

But of course, such contingencies shape not only a society but also one’s life, and, as Haulman notes with an easy smile, his life could have unfolded very differently.

In college Haulman majored in music, attending Florida’s Stetson University on a musical scholarship — that is, until one of those historical contingencies showed up. Halfway through his degree, Haulman happened to sign up for American Studies, an interdisciplinary course that covered American culture, literature, music and history.

“And it became my calling,” Haulman said with a gentle laugh. “When you do something — whether you get paid for it or not — that becomes a calling more than a career. That’s what history was for me. I’d do it anyway. The fact that they paid me, so much the better.”

Haulman’s earliest enthusiasm focused on boats. From the dinghy he rowed growing up in Panama City, Fla., to the first sailboat he helmed at age 11 to the progressively larger sailboats he owned on Vashon, Haulman clearly loves boats. For years, Haulman annually raced in 15 to 18 events, including the legendary Swiftsure race. After he married his wife Pam, a kindergarten teacher at Chautauqua Elementary School, he switched from sailing to motoring, naming his new boat Vashona after one of the Mosquito Fleet vessels built in Dockton in 1921.

About 10 years ago, Haulman helped start the Vashon Park District’s sailing program and still oversees it. He believes it is a great experience for young kids, but even closer to his heart is the second aspect of the program, mentoring the teenage instructors.

“We bring them in at 14, 15 as apprentices; they get certified as instructors at 16. They learn boat maintenance, responsibility and how to teach. … You see them grow up, build skills and gain confidence — that’s as important to me as teaching little kids how to sail.”

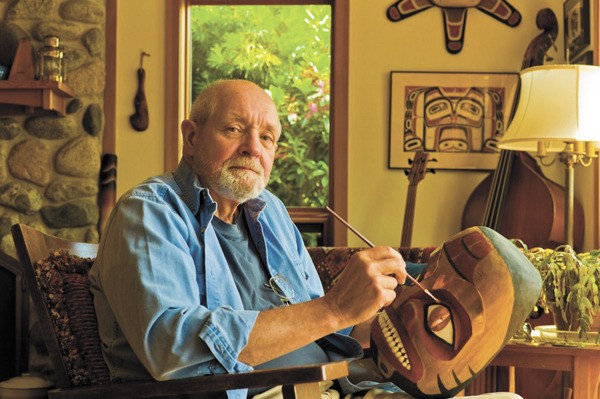

Step into Haulman’s living room and evidence of his other passions reveal themselves. Above the windows, lining the length of the room, is a stunning collection of Pacific Northwest Coast masks, some painted, others inlaid with copper and abalone shell. Haulman carved every one of them.

In the early 1980s, he began teaching Pacific Northwest history, learning much about the region’s Native culture in the process. Inspired by the Nuu-chal-nuth tribe of Clayoquot Sound, Haulman began carving, eventually meeting his primary teacher, Tlingit master carver Israel Shotridge, an Islander with whom he’s developed his masks, bowls, bentwood boxes, drums and other Northwest-style pieces.

Under the masks in a corner shaded from sunlight spilling through the windows, stands an upright wooden bass, Haulman’s constant companion since his teens. Haulman has plucked his way through a variety of musical genres, from his high school jazz band to his college symphony to his current involvement with the Island band Bob’s Your Uncle.

Soft spoken and modest about his accomplishments, Haulman talked about his role as a history professor at Green River, where he taught Pacific Northwest, American and film history since 1989. He’ll continue to lead two study-abroad programs, one in Australia and New Zealand, the other in Clayoquot Sound, plus a leadership program for young women from North Africa and Southeast Asia.

Then there’s Haulman’s most recent effort, bound and ready for release on July 11 — “Vashon: The Natural and Human History of an Island.” It’s the first written history of Vashon since O.S. Van Olinda penned his in 1935.

Haulman collaborated with Islander Jean Findlay. Together they chose numerous photographs from the Vashon-Maury Island Heritage Museum, where Haulman serves on the board, with the goal to tell a more objective account of Vashon’s past than that of Van Olinda.

“Van Olinda’s history is a good first effort,” Haulman said, “but it is very reflective of the times. It’s a raconteur’s history, sort of a pioneer’s recount of the wilderness. He also carried the racist view of his time, denigrating the native people of the Island and ignoring the first permanent settler, a guy named Matthew Bridges.”

Bridges, a logger from a shipping family in Maine, came to the Island in 1865, living first at Paradise Cove and ending up at Tahlequah. Van Olinda, however, ignored him, Haulman noted, choosing a different name for Vashon’s first family. “Bridges was not a union veteran; he was a logger not a farmer, and he married an Indian, so he’s written out of history.”

Haulman and Findlay structured each chapter by asking why the Island has become what it is, looking at each major period. “And Vashon,” Haulman noted, “has gone through some interesting transitions.”

The story that unfolds is a tale of the unforeseen events that shape history — beginning with the 4,000 to 6,000 years the Sammamish Indians dwelled here to a reflection about why the Island once boasted 30 ferry docks, 15 post offices, 14 country stores and 13 school districts.

Haulman spins a beguiling story, complete with local characters and settings, always peppered with dates and illuminated by contingencies. It is a slim book packed with photos, both an easy read and a full account of Vashon’s past.

And with its publication, Vashon’s unofficial historian, the keeper of historical and cultural information and little-known stories, will soon become official.

— Juli Goetz Morser is a freelance writer.