There’s a small but bright piece of news among those on Vashon who pay attention to the tumultuous world of Sudan: Jacob Acier’s mother has returned to her home village in the southern grasslands of her small, war-torn country.

Thanks to the fundraising efforts of a handful of Islanders and Acier’s gumption and determination, Acier was able to wire his mother enough money for her to hire a driver, who carted her in the back of a flat-bed truck from a Ugandan refugee camp where she had lived for years to her former home in Sudan hundreds of miles away.

Six of Acier’s step-siblings left the camp with her for their native home. The Vashon group — calling itself the Jacob Acier Group — also raised enough money for him to arrange the purchase of five cows for his family. The animals are the currency of his people.

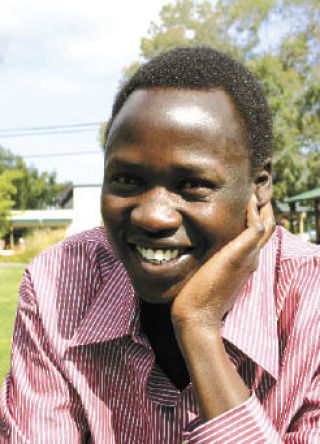

Jacob Acier, who was 7 or 8 when he heard the sounds of marauders rampaging through his village and fled, has captured the hearts of many Islanders with his remarkable story of survival and his personal grace and warmth.

A “lost boy” of Sudan, he came to Vashon last year, in search of work and stability after years as a kind of itinerant refugee, living in different places and holding down a variety of jobs.

He now has a steady job at Sawbones, where he routinely works overtime to bring in extra cash. He has a group of friends and supporters who meets with him often. He even has a kind of family on Vashon; Islander Constance Walker, a key player in his life, has become his touchstone, he says. He calls her “Auntie Connie.”

But most important, Acier — who discovered that his mother was living in a refugee camp after another “lost boy” showed him her photo — has not only reconnected with her. He has also begun the hard work of helping her to rebuild her life — an effort that is unfolding across the continents, with the help of several Islanders and by his own utter determination to do what he can as the eldest son and only U.S. resident in his huge, extended family.

“I feel responsible for them,” he said.

“The life in the camp is no good,” he added. “My mother was very sick. That’s why I didn’t want her to be in the camp any longer.”

He also seems a bit dazed by the outpouring he’s experienced since he moved to Vashon; a story about him that appeared in The Beachcomber has been posted on community bulletin boards and elsewhere and has been forwarded to organizations and individuals off-Island as well. As a result, he said, strangers regularly approach him on the street, asking how they can help. People he’s never met wave and call out, “Hello, Jacob.”

A young girl recently came up to him and said her father had her read the news story about him and encouraged her to keep in mind the hardships others face. Other children have approached him saying they’ve been collecting coins to support his efforts.

“I feel happy. I feel so welcomed,” he said during a recent interview at Cafe Luna, shaking his head in wonder as he spoke. “People say that to me all the time — ‘we want you to be here.’”

“People ask me why I smile,” he added, flashing one of his radiant grins. “I smile because God is really great.”

Shortly after his arrival to Vashon last fall, a small group of Islanders began to rally around him, moved, as Kevin Joyce, a key player in the group, said, “by his tenacity of spirit.” Members of the group held a fundraiser at the Methodist Church in April and have made a number of personal appeals, Joyce said. As a result, they’ve raised around $10,000, nearly all of which they’ve spent.

The expenses have been numerous, Joyce and Walker said.

They discovered, for instance, that when he arrived in the United States five years ago, he hadn’t paid the $800 airfare, something that Walker said has been required of the “lost boys” who came to this country as refugees. Acier is eager to travel to Sudan to see his mother, but he can’t go until he gets travel documents, and he couldn’t get those documents until his outstanding airfare was paid. So the group covered that, Walker said.

His mother and step-siblings’ transport to Sudan cost another $1,500, and along the way his mother stopped at a village where her uncle had died; a funeral and the butchering of a steer were in order; that was another $500, said Walker.

Handling all of these things — finding a safe way to get his ailing mother home, buying cattle, dealing with the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service — has felt daunting, Joyce said. No one in the group has experience in the complexities of a refugee’s life or the workings of an African country’s economy, he said.

But they were struck by Acier’s clarity; all along, he’s been explicit about what he’s wanted to see happen, Joyce said. They also knew that if Acier could overcome the hurdles he’s faced to make a new life for himself in the United States, surely they could figure out how to raise some funds and get the money to his family in Africa.

“This is the place where Jacob’s story ends up being an inspiration to us all,” Joyce said.

The process has also been remarkable, Joyce and Walker noted.

Acier has gotten money to his mother by wiring it through a Somali restaurant in Tukwila, which has a connection with Amal Express, a Somali company that provides such services. The funds end up in Wau, a town in southern Sudan not far from Acier’s home village. There, his brother has picked it up, confirming by telephone calls that he has indeed received it.

And in some instances, the group has felt that there should be a certain order to things — getting a home for his mother built, for instance, before arranging her return to her village — only to have events unfold far differently. When Acier found someone who would transport his mother, for instance, he jumped on it, asking the driver to move forward and then notifying the group his mother was en route and needed to pay the driver.

“It’s been a crazy ride,” Joyce said. “It’s just incredibly enlightening to be a part of something that happens with its own logic and with only a little of our own control over it.”

Those involved also say it’s been deeply moving to work with Acier. It’s rare, they note, to have such a direct experience of helping someone rebuild a life torn apart by civil war, poverty and racism. And then there’s Acier himself, who has such presence, strength and warmth that those working on his behalf say they’ve come to love him.

“I guess we have five sons now, instead of four,” said Walker.

But the group is hardly done with its work. Still before them is helping Acier find a way to travel to Sudan, so he can see his mother. It’s been 15 years since he ran from his village; now only 23, Acier has spent some two-thirds of his life as a refugee.

“She asked me, ‘How tall are you?’” Acier said, recalling a recent telephone call with his mother. “I told her, ‘I’m 6-foot-4. I grow tall.’ She’s happy to hear that. But she doesn’t understand what it means. She wants to see me.”