Six months after an island woman says she was drugged and raped on Vashon, she has stepped forward to tell her story and bring light to a new island program aimed at reducing violence of all kinds, especially drug-facilitated sexual assault.

The program, called Vashon SAFE (sexual assault-free establishments), is slated to launch this week and includes a core group of island businesses — bars, restaurants and others — whose owners or managers have joined together to train their staffs in intervention techniques useful in a variety of difficult situations. The training also includes information on understanding and preventing sexual assault, particularly related to drugs and alcohol.

More businesses are expected to follow as the program becomes established, according to DOVE Project Executive Director Betsey Archambault, who spearheaded the effort last fall. Last week, she said she has high hopes for the program, which is one-of-a-kind and created by DOVE and the business owners involved.

“Vashon SAFE businesses know that people could use their establishments (or any other establishments) for improper purposes and are taking a stand and making changes to stop sexual violence,” Archambault said.

The roots of the program go back to an early Saturday evening in October, when islander Julia Anderson was looking forward to seeing her partner, Craig Sutherland, and other friends in “Darkness Illuminated,” a show at Vashon Center for the Arts. The night ended with a crime that has had far-reaching effects for Anderson and, potentially, the broader Vashon community. Anderson, a mother of two young children and a former teacher who now works at the Open Space for Arts & Community, recounted her experience recently, hoping to let people know that drug-facilitated sexual assault happens on Vashon as well as the steps some community members are taking to prevent it from happening again.

The night of the show, Anderson left her children in the care of her father at her Point Robinson home, but before she went to the theater, she stopped by an island establishment for a glass of wine. Before she left the business, which was nearly empty, she went to the restroom and headed to the theater shortly after.

“I left and felt fine, and I was excited to go see the show,” she said.

Anderson, who grew up on the island and knows many people in the community, mingled in the theater lobby. There, she also met up briefly with Sutherland, who introduced her to one of his friends. It was then that Anderson started having trouble speaking. By the time she took her seat, she knew something was wrong and realized she had no memory of parking her car. She felt a sense of panic, she said, as though something was profoundly wrong with her brain.

Feeling that she could not remain in the theater until she located her car, she left. From events she has been able to reconstruct through text messages, friends and sparse flashes of memory, she believes she must have wandered in the dark for 20 minutes or more. She found her car in front of the Vashon Island Coffee Roasterie, Halloween pumpkins aglow, and recalls sitting inside it, glad to be safe. She knew she was acting strangely, she said, but she did not understand why. Her phone indicates she texted Sutherland, telling him she was heading into town and would be back in a minute. This did not make sense, she said, as she had wanted to see the show and stay for the after-party.

“At no point did I think I might have been drugged. I thought something weird was happening to my brain. I was embarrassed, and I did not want to be seen like how I felt. I wanted to run and hide,” she said.

There her memory of the night stops.

“It felt like I was shut down, like a robot shutting down. And then it just ends,” she said.

Her next full memory is of 5 a.m. the next day when she woke next to a strange man, not knowing if she was on Vashon or not — and terrified.

“I was so glad to be alive and had to keep myself alive, that was my first thought,” she said.

She woke the man and asked him to help her; he complied, nicely, and told her he knew where her car was and drove her to it.

Driving home was difficult, she said. Her vision and speech were impaired and she had a severe headache. She was hurt physically; her clothes were ripped, and it was clear, she said, that she had not been in “a good place with someone who had good intentions.”

She had received countless frantic text messages and phone calls from her dad and many friends. She stopped briefly at Sutherland’s home. He had been out in the night searching for her and had been told she had drunk too much and a man had driven her home. She left his house quickly: Her primary concern was getting home before her kids woke up, she said. When she arrived, she first saw her dad.

“I have never felt more horrible in my life than looking at him and what he had gone through,” she said.

Her father, Scott Anderson, recalls his fear that night — and his concern when she returned.

He had come over the night before, intending to stay over and care for his grandchildren, ages 8 and 4. He put them to bed but woke at midnight, alarmed that Julia was not home yet. Worrying and unable to leave the children alone, he called Sutherland.

“I was going nuts. This is like every father’s worst nightmare,” Scott Anderson said, adding that he called the police and area hospitals trying to locate Julia. “This was totally out of character for her.”

A former emergency medical technician, he recognized she was in bad shape when she returned and thought she might have had a stroke. The kids went with their dad, and he took her straight to the Swedish hospital emergency room, where her bruises were evident and a toxicology test was conducted.

Her medical records from that day make clear why Julia Anderson had been so impaired: “Rohypnol detected,” they state.

With that news, Scott Anderson said, the nightmare grew worse.

Rohypnol is commonly known as a date-rape drug and is a powerful sedative that causes motor skill impairment, muscle relaxation and memory loss, among other effects.

Julia said the medical staff asked her if she wanted to undergo a rape exam, but she declined. It is a decision she regrets, and she said she wishes she would have had an advocate to help her understand the ramifications of that decision, including on pursuing legal options.

“It would have been another tool, and I wish I had it in my toolbox,” she said.

In the days that followed, Julia Anderson and her friends gathered more of the story of that night through talking to people who witnessed parts of it or were directly involved. They know that when she left the theater, she went to another establishment, and although she was impaired to the point of not being able to walk, people bought her drinks. A ride was arranged for her, but the man did not take her safely home, but to his house after first — she’s been told — assaulting her in his vehicle.

Scott Anderson says he slept on Julia’s floor for weeks afterward so that she was never alone. He credits one of her co-workers with taking her to DOVE for assistance. Julia, who has not yet filed a police report but still may, threw herself into healing, she said. She also explored her legal options with islander Jessica DeMarois, an attorney who works for the YWCA and specializes in sexual violence cases. Julia learned that prosecution of her case was unlikely.

DeMarois says cases like Julia’s are “unfortunately fairly common,” but she doubts that the King County Prosecutor’s Office would have brought charges.

“I would have been surprised,” DeMarois said. “They are reluctant to prosecute these kinds of cases.”

In fact, a Seattle Weekly article last December stated that charges are never filed in more than half of all sex-crime cases that come into the King County’s Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, and that percent declines sharply when alcohol is involved.

“Because the evidence can be so limited, and because juries have long been reluctant to convict when a rape victim had been drinking, prosecuting this form of assault is especially, and in some cases, prohibitively, difficult,” the article states.

DeMarois also noted it is uncommon for someone who was drugged to have the proof that Julia does.

“It’s incredibly rare to get this piece of paper that says, ‘Yes, we have proof that it happened.’ You’d think on Vashon it would not happen, but it obviously did,” she said.

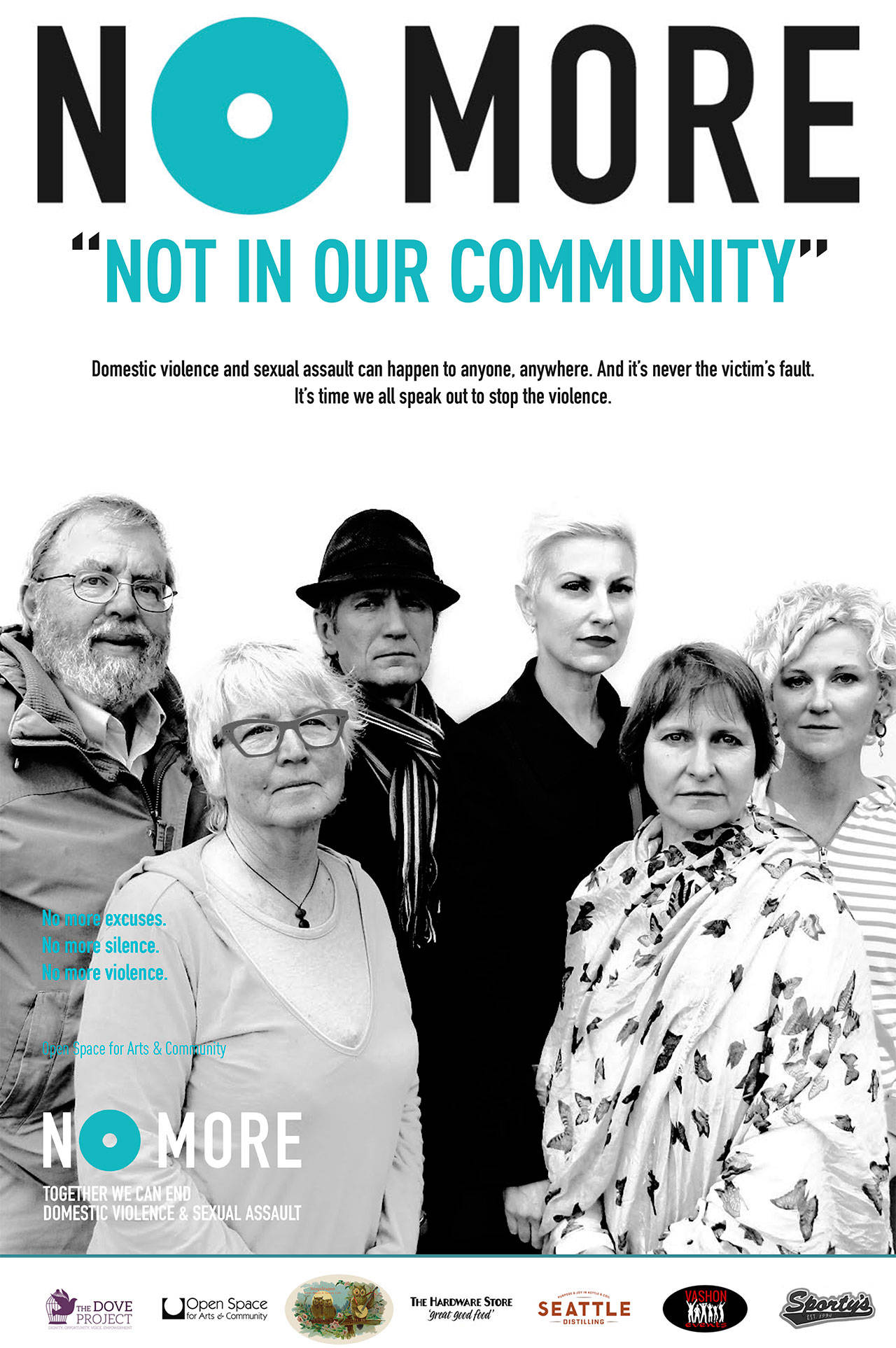

With limited recourse, Julia Anderson has turned her attention to issues she can control and was drawn to the Vashon SAFE program. She has gone through the training and will use the information in her work when the Open Space re-opens with a liquor license. More broadly — and more personally — she says she wants to be an ambassador for the program. In part, she expects to be involved with businesses regarding what works and what doesn’t to make the program truly effective. And she expects to be a bridge to others. After the story of her assault first spread in the community, many people shared their own assault stories with her, she said. She sees more of that ahead.

“What stories have not been told? That is one of my important roles, to give voice to stories hiding in the darkness,” she said. “I want the darkness illuminated. I want to shed light.”