Pictures, lately, have consumed my life. Pictures everywhere, in every corner of my office, in huge envelopes in my car, piled high on the desktop, splayed as tiny icons across my computer screen, in albums stacked next to the front door — literally thousands of pictures, and the imperative to look at every shot, to divine a connection between decades of photo-taking and the phenomenon that has been my parents’ relationship for what will be 60 married years on June 14 of this year.

At the same time I sift through family pictures, I am immersed in preparations for an incredible show at the Vashon- Maury Island Heritage Museum, an undertaking with a picture mania of its own — except the pictures in this case are mostly in one man’s house in Edmonds, hundreds of them hanging in elegant old frames on wall after wall, hundreds more in archival cabinets; pictures generated by one man that represent another kind of passion — that of Norman Stewart Edson and his relationship with his camera and, for a part of his life, Vashon.

A huge chunk of that collection is coming on loan to the museum, which is a coup for the Vashon-Maury Island Heritage Association as well as the lucky Islanders who get to see it.

Against the backdrop of those Edson masterpieces, unexpected little truths, like shiny nuggets in a pan of sand, emerge about the family shots I’ve been looking at — truths that expose the way we view pictures when we’re privy to the missing narrative and how that truth can elevate those pictures to the level of art in the eyes of the knowing beholder.

In the case of Norman Edson’s pictures, the viewer has to rely on his or her own imaginings for the narrative, which is actually half the fun. But the truth is probably within a not-so-distant reach, because many of the settings are so familiar. It’s a high art opportunity to look at our Island and superimpose our modern perspective on this talented man’s long-ago love affair with a landscape we know so well.

Among the Edson photos are two self-portraits that inspire bookend musings about the truth of the man himself. The first features a handsome young Edson sitting between two Tulalip women who have momentarily stopped their weaving to accommodate his vanity. Is his modest smile an expression of deference for these women’s own artistry or a hint at his awareness of the privilege his camera affords him to waltz into people’s ordinary moments and start snapping away? Did those women indulge him because they understood that this would be a white man who would treasure, not trash, their legacy? It’s a provocative flash of time captured for future generations to ponder, but only those three people will ever know what the truth was in the real time of that camera’s shutter.

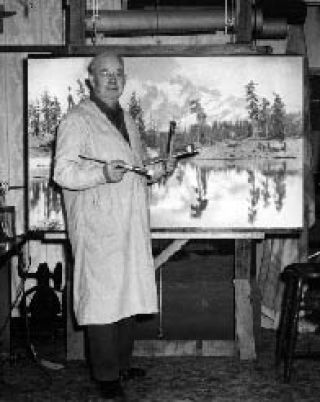

The other is an image of the photographer as an old man in his studio surrounded by several of the works that are today among the most valuable bearing his signature. He wears a paint-spattered smock and a look of modest satisfaction, clearly aware by this point in his career of his place in the larger photographic canon. Is he satisfied because his art has been a source of soulful nourishment or because he knows “The Sun’s Last Glow,” his famous shot of Mount Rainier framed by firs, has paid off his mortgage and he’ll never have to shoot another wedding as long as he lives? As you look at the stunning variations of medium he applied to “The Sun’s Last Glow,” it seems he really does adore his subjects and feels no need to be bashful about expressing that passion.

In the process of curating an anniversary album for my parents, I thought I would find the truth of their relationship in the most beautiful photos everyone had shot over the past seven decades. There were the classics — the graceful college portrait with shoulders bared, the handsome uniformed soldier, the line-up on the candlelit altar, the various formal studio sittings each time they added a little member to the family and the ubiquitous, well-organized shots of the two of them dressed to the nines for some special occasion. In the end, very few of those shots made the cut. The ones that ended up in the album, a volume that aims to explain a 60-year collaboration, were the shots that grabbed me at the subconscious level and wouldn’t let go.

One tiny yet powerful print was a picture my dad snapped with his Brownie in the mid-1940s of his future father-in-law astride a horse. It’s a hint at my grandfather’s manliness, a side of him I’d never really seen. A sweet sensitive man who played a mean

fiddle, Grandpa would starve to death before he asked for anything at the table. What I treasure most about this photograph is that it portrays my grandfather as a most about this photograph is that it portrays my grandfather as a vigorous horseman in full control of something bigger than himself, as opposed to the dispirited prisoner of a stroke I saw hopelessly trapped in a chair for the last years of his life. It makes me think of my grandmother, the model of wedded devotion, who took loving care of that man until she herself ended up in a nursing home. Did my dad grasp what a work of art he was making as he clicked the shutter that day? Did he know he was viewing his future wife’s ability to sit tall in life’s saddle in the face of the many rocky paths they would ride together?

Another shot stops me in my tracks every time I look at it and makes epic understatement of the old saw about pictures equating to 1,000 words. Wildly enough, it’s a portrait of a batch of deviled eggs my sister made. That sounds silly, until you know that deviled eggs were our brother Dave’s favorite food on earth, and after MS claimed his life in 1993 a plate of deviled eggs became the one tangible way to bring his spirit back to the table. What I see in that picture is not eggs, but the fact that we all prepare that dish with reverence. It evokes the power of dependence on a trusted partner for sheer survival, as I recall the memory of my parents holding on to one another next to Dave’s casket.

The picture that puts the exclamation point on the album is one taken when our parents visited us on Vashon last summer. We’d spent the day baking, gardening and reveling in the gift of their visit and were enjoying a glass of champagne as the sun began to drop. When I pulled out the camera, my mother made one of her characteristic smart remarks at Dad’s expense — a moment that epitomized their entire relationship, her head thrown back in a triumphant guffaw, my dad holding his glass up to her in a congratulatory toast, smiling that “I’m helpless not to love you” smile. My brilliant, generous to a fault, wickedly fun Mom takes no prisoners, and my dad is her adoring match. They are tenacious in their devotion to one another, and that photograph is lightning captured in a bottle.

The modern world is lousy with cameras, and with more and more sophisticated technology the idea that anyone can make pictures into Art is one that seduces amateurs and rankles pros. I look at the works of Edson and am in awe of his capacity to use his lenses to see the art, then transcribe it with the aid of a clumsy, old-fashioned box that filled an entire compartment of his canoe.

I look at the Brownie shots my parents took, snapped with a pragmatism befitting a generation that had lost everything and knew the true meaning of the word “ephemeral.” In those tiny prints I witness art that is mostly lessons in humanity.

I look at the thousands of photographs our modern family has made over the past decades, and the art I see isn’t the pictures — indeed, many of the photos are appallingly out of focus. None would be considered art at any level, much less anything near Edson’s brilliant mark. The art I see there is the art my memory brings to the viewing, the nurturing family history captured within a deceptively flat dimension. I realize it will only be art to those of us who were connected to that history, but in the end what else matters? Art is, in the end, what the viewer brings to the viewing.

See Edson’s wonderful art at the heritage museum this month. Bring your imagination and fill in a narrative. Then return home, look at your own pictures and revel in the art that is your family’s visual heritage. High art or deeply personal, it’s all part of that big portrait called history, a picture that endures as art of some import to someone after each click of the shutter.

— Rebecca Wittman serves on the board of the Vashon-Maury Island Heritage Association.